Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791)

One day when I* was sitting at the pianoforte playing the ‘Non più andrai’ from Figaro, Mozart, who was paying a visit to us, came up behind me; I must have been playing it to his satisfaction, for he hummed the melody as I played and beat the time on my shoulders; but then he suddenly moved a chair up, sat down, told me to carry on playing the bass, and began to improvise such wonderfully beautiful variations that everyone listened to the tones of the German Orpheus with bated breath. But then he suddenly tired of it, jumped up, and, in the mad mood which so often came over him, he began to leap over tables and chairs, miaow like a cat, and turn somersaults like an unruly boy.

*Karoline Pichler (1769-1843); Viennese novelist.

——-

Mozart fortified himself with a glass of wine or punch when he was in the throes of composition. In one of his apartments his immediate neighbour was Joh. Mart. Loibl, who was musical and a Freemason, [and] consequently intimate with Mozart; he had a well-filled wine cellar, of the contents of which he was never sparing in entertaining his friends. The partition wall between the houses was so thin, that Mozart had only to knock when he wished to attract Loibl’s attention; whenever Loibl heard the clavier going and taps at his wall between the pauses, he used to send his servant into the cellar, and say to his family, ‘Mozart is composing again; I must send him some wine.’

——

Michael Haydn* had been ordered by the Archbishop to compose some duets for violin and tenor, perhaps for his special use, but owing to a violent illness, which incapacitated him for work during a lengthened period, he was unable to finish them; the Archbishop thereupon threatened to deprive him of salary. When Mozart heard of the difficulty he at once undertook the work, and, visiting Haydn daily, wrote by his bedside to such good purpose that the duets (K423, 424) were soon completed and handed over to the Archbishop in Haydn’s name.

*(1737-1806); Salzburg composer, brother of the more eminent Joseph.

——

The next two anecdotes are recounted by Wenzel Swoboda, double-bass player in the Prague Opera House Orchestra.

At the final rehearsal [in Prague of Don Giovanni] Mozart was not at all satisfied with the efforts of a young and very pretty girl, the possessor of a voice of greater purity than power, to whom the part of Zerlina had been allotted. Zerlina, frightened at Don Giovanni’s too pronounced love-making, cries for assistance behind the scenes (but) in spite of continued repetitions, Mozart was unable to infuse sufficient force into the poor girl’s screams, until at last, losing all patience, he clambered from the conductor’s desk on to the boards. At that period neither gas nor electric light lent facility to stage mechanism. A few tallow candles dimly glimmered among the desks of the musicians, but over the stage and the rest of the house almost utter darkness reigned. Mozart’s sudden appearance on the stage was therefore not noticed, much less suspected, by poor Zerlina, who at the moment when she ought to have uttered the cry received from the composer a sharp pinch on the arm, emitting, in consequence, a shriek which caused him to exclaim: ‘Admirable! Mind you scream like that tonight!”*

The evening before the production of Don Giovanni at Prague, the dress rehearsal having already taken place, he said to his wife that he would write the overture during the night if she would sit with him and make him some punch to keep his spirits up. This she did, and told him tales about Aladdin’s lamp, Cinderella, etc., which made him laugh till the tears came. But the punch made him sleepy, so that he dozed when she left off, and only worked as long as she told tales. At last the excitement, the sleepiness, and his frequent efforts not to doze off were too much for him, and his wife persuaded him to go to sleep on the sofa promising to wake him in an hour. But he slept so soundly that she could not find it in her heart to wake him until two hours had passed. It was then five o’clock. At seven o’clock the overture was finished and in the hands of the copyist.

The ink, Swoboda recalled, was hardly dry on some of the pages when they were placed on the desks of the orchestra. A rehearsal was impossible. Nevertheless, the overture was played with a spirit which not only roused the enthusiasm of the audience to the highest pitch, but so greatly delighted the illustrious composer that, turning to the orchestra, he exclaimed, ‘Bravo, bravo, Meine Herren, das war ausgezeichnet!’ (Bravo, bravo, gentlemen, that was admirable!)

——

Lorenzo da Ponte (1749-1838); Mozart’s librettist, recalls

The Emperor sent for me [in Vienna] and told me that he was longing to see Don Giovanni…. Need I recall it?… Don Giovanni did not please! Everyone, except Mozart, thought that there was something missing. Additions were made; some of the arias were changed; it was offered for a second performance. Don Giovanni did not please! And what did the Emperor say? He said, ‘That opera is divine; I should even venture that it is more beautiful than Figaro. But such music is not meat for the teeth of my Viennese!’

I reported the remark to Mozart, who replied quietly, ‘Give them time to chew on it!’

——

The success [of The Magic Flute] was not at first so great as had been expected, and after the first act Mozart rushed, pale and excited, behind the scenes to Schikaneder* who endeavored to console him. In the course of the second act the audience recovered from the first shock of surprise, and at the close of the opera Mozart was recalled. He had hidden himself, and when he was found could [only] with difficulty be persuaded to appear before the audience, not certainly from bashfulness, for he was used by this time to brilliant successes, but because he was not satisfied with the way in which his music had been received.

*Emanuel Schikaneder (1751-1812); German theatre manager and playwright, librettist of The Magic Flute.

——

Schenck* relates that after the overture, unable to contain his delight, he crept along to the conductor’s stool, seized Mozart’s hand and kissed it; Mozart, still beating time with his right hand, looked at him with a smile, and stroked his cheek.

*Johann Schenck (1753-1836); Austrian composer, teacher of Beethoven.

——

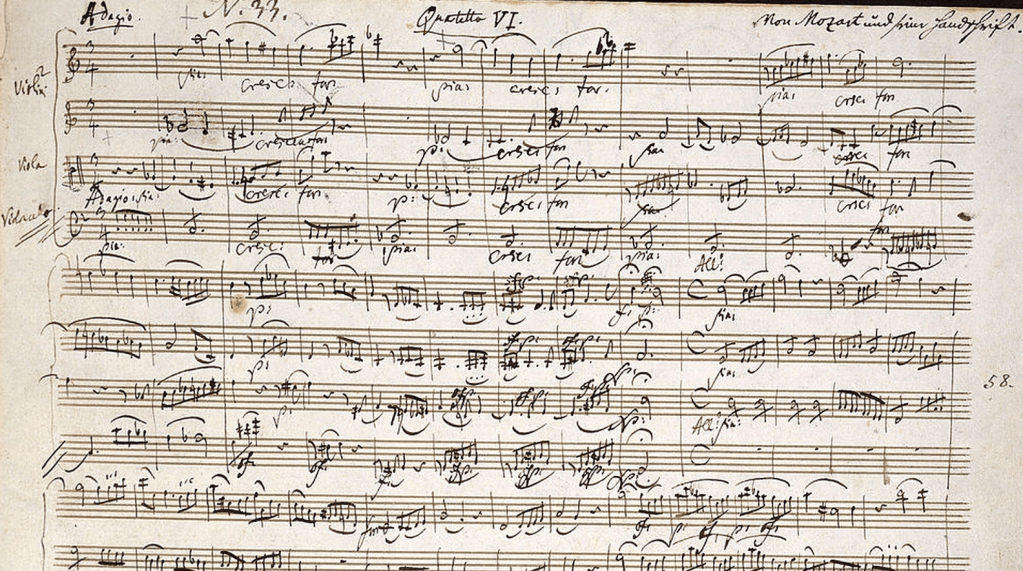

Italian ears were slow to approve the piquant chromatic harmony of the Germans, or to perceive in it the source of unnumbered beautiful effects in instrumental music. When [the music publisher] Artaria sent [Mozart’s six] quartets to Italy they were speedily returned with the excuse, ‘the engraving is full of mistakes.” Nissen relates that the Hungarian Prince Grassalkowitsch was one day hearing them performed by the musicians of his chapel, when he called out repeatedly, ‘You are playing wrong;’ and on the parts being handed to convince him of the contrary, he tore them up on the spot.

——

Beethoven arrived in Vienna in the spring of 1787 as a youth of great promise and was taken to play before Mozart. Assuming that his music was a showpiece specially prepared for the occasion, Mozart responded coolly. Beethoven begged him to state a theme on which he could improvise and began playing as if inspired by the Master’s presence. Mozart became engrossed. Finally he rejoined his friends in the next room and pronounced emphatically, ‘Keep your eyes on that young man. Some day he will give the world something to talk about.

——

Once, when a new quartet of Haydn’s was being performed in a large company, Kozeluch,* standing by Mozart, found fault, first with one thing and then with another, exclaiming at length, with impudent assurance, ‘I should never have done it in that way!’ ‘Nor should I,’ answered Mozart; ‘but do you know why? Because neither you nor I would have had so good an idea.’

*Leopold Kozeluch (or Kozeluh, 1747-1818); Czech composer who refused to occupy Mozart’s post in Salzburg but later accepted his court position in Prague.

——

When he was traveling with his wife through beautiful scenery, [Mozart] used to gaze earnestly and in silence on the scene before him; his usually absent and thoughtful expression would brighten by degrees, and he would begin to sing, or rather to hum, finally breaking out with: ‘If I could only put the subject down on paper!’ And, when [Constanze] sometimes said that he could do so if he pleased, he went on: ‘Yes, of course, all in proper form! What a pity it is that one’s work must all be hatched in one’s own room!’

Leave a reply to Meet Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart through anecdotes (1/3) – UP CLOSE AND CLASSICAL Cancel reply