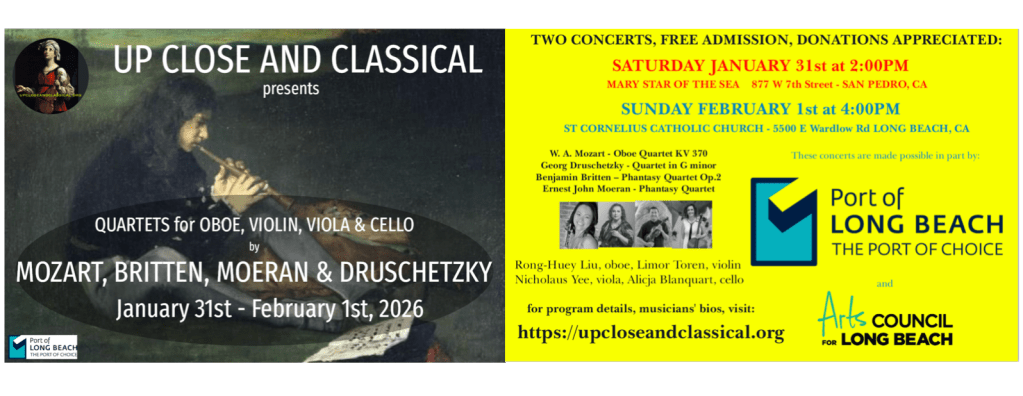

Our January 31st-February 1st concerts will feature the oboe quartet in G minor by Georg Druschetzky (1745-1819), one of the ten oboe quartets he composed in 1807-1808. Little is known about this composer, and even less of his music was published during his lifetime. Yet, his amazing music is now being published and recorded: Druschetzky’s music is then both new, yet classical. The little we know about Druschetzky prompts comparisons with Josef Haydn. Both were born in small villages in circumstances unlikely to lead to an illustrious career in music. Both were musician-servants most of their life. Haydn’s “break” was made possible through his ability to experiment with a full orchestra at his dayjob. Druschetzky was an oboist and a timpanist, hence his “break” being delayed by a few centuries…

In 2019, Oboist Eduard Wesly recorded all of Druschetzky’s ten “late” oboe quartets (see covers below) and here is what he wrote about them in the CD cover.

————

DRUSCHETZKY’S PRESUMED DEAD END

(Or: how those who enter the maze of music history can lose their way in interesting paths.)

An important element of all art and entertainment is taking an audience by surprise and playing with what it expects. In the second half of the eighteenth century, this aspect of music reached a level more elevated than ever before, as a result of developments in social and musical history beyond the scope of this introduction.

Joseph Haydn was the High Priest of the unexpected. The world of his music – with its irregular structures, its harmonies that broke with convention, its sudden dynamic effects that startled even connoisseurs, its rhythmic variety and its sometimes unusual instrumentation – seized listeners’ attention just as a sumptuous fireworks display holds our gaze. The switch of tenses in the last sentence is deliberate. While we may not hold the same opinion of fireworks as our eighteenth-centurym ancestors, the difference is minimal compared with the change in our ability to understand the battery of surprises that is Haydn’s music.

To appreciate a joke, one needs to understand its context. If a musical surprise is to work, the standard rhythmic, melodic, harmonic or formal patterns must be second nature to listeners. Not only do today’s audiences have quite different backgrounds, interests and of course ears from Haydn’s contemporaries, but we are above all scarcely attuned to what counted as ‘standard’ in the second half of the eighteenth century, so that most of us hardly notice Haydn’s supreme mastery of surprise.

This particular path of music history reached a dead end with the music of Beethoven, who knew how to build a surprise and often did so, but only in support of other musical-dramatic effects, not as an end in itself, and unfortunately without Haydn’s subtle humour. However, in Beethoven’s time, a last few composers still kept up the classical style, playfully putting sounds together to entertain and surprise their audience. Mention should certainly be made here not only of composers such as

Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Johann Leopold Eybler, but also of Georg Druschetzky.

We do not know where he studied composition, or indeed whether he had any formal training. He must, however, have known the works of Haydn and Mozart well, for he arranged several of them for wind ensemble. What is unusual about Druschetzky is that in his later years his compositional style underwent an explosive development, for which, from our distant point of view, there is no satisfactory explanation. The works he composed in his early years show a moderate and unexceptional creativity. As the musicologist Szendrei Janke says in her introduction to Volume 4 of the Musicalia Danubiana (Budapest, 1985), which contains partitas for wind instruments by Druschetzky, »Druschetzky’s works are what one might call conventional creations,

informed by a knowledge of the stereotypes of the high classical style. (…) His partitas are well-constructed, pleasant-sounding compositions, and reflect that period of classical style in which the forms and expressions of the great masters became plain spoken vernacular.« Ulrich Rau, in turn, writes of Druschetzky, in Die Musik in

Geschichte und Gegenwart (1989), »His work, composed in a fresh musical style and rich in classical sensibility, essentially served the world of social music-making.«

However, these descriptions in no way fit the ten oboe quartets that Druschetzky composed in 1807–1808 in Ofen (today Buda). There is no comparison between these works and the Partitas, Masses, Concerti for six, seven or eight timpani, etc.

which represent the composer on YouTube, Spotify or CD today. In these late oboe quartets, Druschetzky in his own way often reaches similar heights as the surprise artist Haydn.

About the G minor quartet :

The unusual key of the Quartet in G minor (the only late oboe quartet to be written in the minor) lends high drama to its opening and closing movements. In the central movement, an Andante with variations, the B-A-C-H (B flat-A-C-B natural) theme is introduced with exquisite lightness of hand. Also, curiously enough, my colleagu-

es and I even lighted on four bars in this movement that foreshadowed the tango. The last movement is characterised by a chromaticism so sudden and violent as to

be almost insane.

Click on below image for details and directions to the concerts (FREE ADMISSION):

Leave a comment