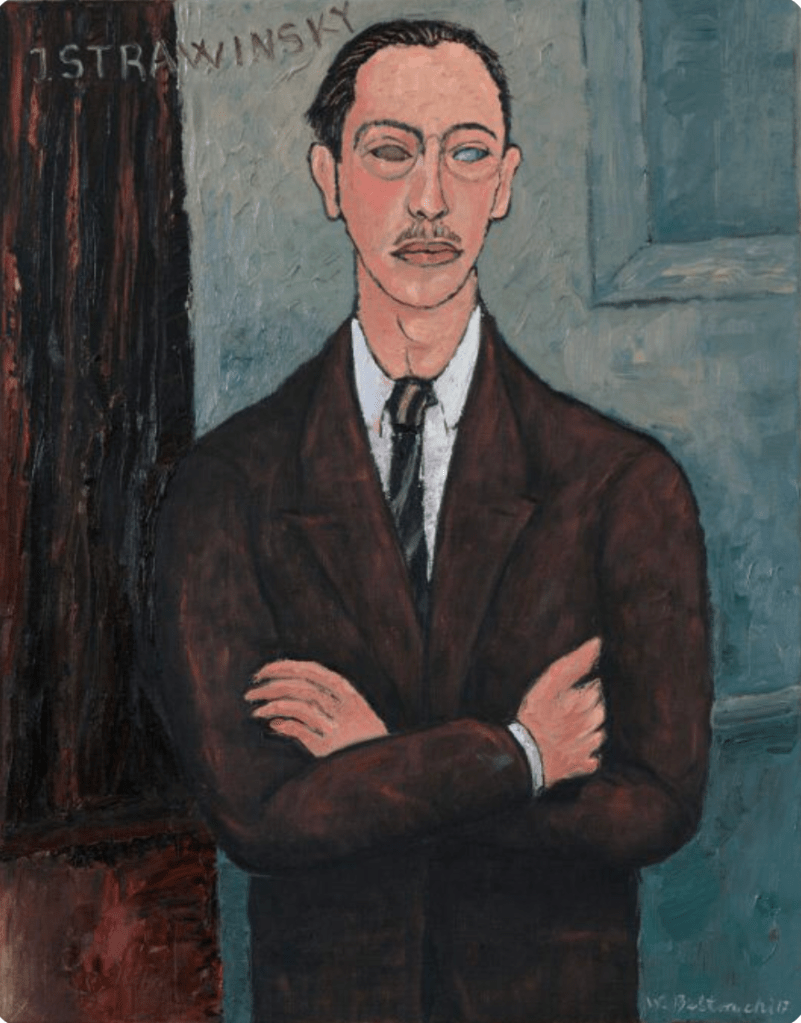

Igor STRAVINSKY (1882-1971)

Born in St Petersburg, Stravinsky made his mark with three Paris ballets commissioned by Diaghilev; the third, Rite of Spring, announced a new era in music. But in mid-life Stravinsky adopted a neo-classical style and in his last years turned to Webernian serialism.

——

The young Stravinsky took a new composition to Rimsky-Korsakov. ‘This is disgusting, Sir,’ said his teacher, ‘No, Sir, it is not permissible to write such nonsense until one is sixty.’ Rimsky remained in a bad temper all day, and at dinner complained to his wife, “What a bunch of nonentities my pupils are! Not one of them is capable of producing

a piece of rubbish such as Igor brought me this morning.”

——

On 29 May 1913, at the Champs-Élysées Theatre, the Sacre du Printemps was performed for the first time, on the very anniversary of the première of Faune, for Diaghilev was superstitious. I* wondered what the reaction of the brilliant, excited audience would be. I knew the music of Sacre, and had seen bits of the dancing from back stage during the last rehearsals, I thought the public might fidget, but none of us in the company expected what followed. The first bars of the overture were listened to amid murmurs, and very soon the audience began to behave itself, not as the dignified audience of Paris, but as a bunch of naughty, ill-mannered children.

One of the witnesses, Carl van Vechtent** wrote about this memorable evening:

A certain part of the audience was thrilled by what it considered to be a blasphemous attempt to destroy music as an art, and, swept away with wrath, began, very soon after the rise of the curtain, to make cat-calls and to offer audible suggestions as to how the performance should proceed. The orchestra played unheard except occasionally, when a slight lull occurred. The young man seated behind me in the box stood up during the course of the ballet to enable himself to see more clearly. The intense excitement under which he was labouring betrayed itself presently when he began to beat rhythmically on the top of my head with his fists. My emotion was so great that I did not feel the blows for some time.

Yes, indeed, the excitement, the shouting, was extreme. People whistled, insulted the performers and the composer, shouted, laughed. Monteux threw desperate glances towards Diaghilev, who sat in Astruc’s box and made signs to him to keep on playing. Astruc in this indescribable noise ordered the lights turned on, and the fights and controversy did not remain in the domain of sound, but actually culminated in bodily conflict. One beautifully dressed lady in an orchestra box stood up and slapped the face of a young man who was hissing in the next box. Her escort rose, and cards were exchanged between the men. A duel followed next day. Another society lady spat in the face of one of the demonstrators. La Princesse de P. left her box, saying ‘I am sixty years old, but this is the first time anyone has dared to make a fool of me.’ At this moment Diaghilev, who was standing livid in his box, shouted, ‘Je vous en prie, laissez achever le spectacle’ [please let them finish the show].

*Romola Nijinsky; wife of Vaslev Nijinsky (1889-1950), dancer and choreographer of Rite of Spring.

**(1880-1964); American music and dance critic.

The conductor, Pierre Monteux (1876-1964) remembers:

‘You may think this strange, but I have never seen the ballet. The night of the première, I kept my eyes on the score, playing the exact tempo Igor had given me and which, I must say, I have never forgotten. As you know, the public reacted in a scandalous manner.

They filled the new Champs Elysées Theatre to overflowing, manifested their disapprobation of the ballet in a most violent manner.

The gendarmes arrived at last. Well, on hearing this near riot behind me I decided to keep the orchestra together at any cost, in case of a lull in the hubbub. I did, and we played it to the end absolutely as we had rehearsed it in the peace of an empty theatre.

After that performance, we played it five times, and five times the

public reacted in the same way.

We played Le Sacre a few times in London to very polite audiences, obviously bent on showing greater sophistication in regard to music and ballet than Paris. Then, as the saying goes, the work was ‘shelved’.

A year later I suggested to Stravinsky that I programme Le Sacre alone in concert. I had not seen the ballet, but friends had described it to me and I was convinced half the manifestations were rebellion at a new form of choreographic art. Stravinsky agreed and, before a theatre completely sold out, with everyone who was anyone in Paris

musical circles in attendance, the work was performed. My mother box and Camille Saint-Saëns sat with her. She told me afterwards that the great French composer did nothing but repeat over and over, ‘Mais il est fou, il est fou! He is crazy, he is crazy!’ As

the work progressed, Saint-Saëns became very angry, as much with me I believe as with Stravinsky, and left in high dudgeon. The reaction of those musicians who had played the première of the work was very different; many said to me, “That music has already aged!”

——

When Stravinsky’s mother visited him from the Soviet Union in 1922, she refused to acknowledge his fame in western Europe. They quarrelled violently in the presence of George Antheil, who saw Stravinsky come close to tears because his mother had reproached him for not composing like Scriabin. Stravinsky said he hated Scriabin. ‘Now, now, Igor,’ said Mrs Stravinsky, ‘you haven’t changed a bit – you were always contemptuous of your betters.’

——

Proust approached Stravinsky at a party after the 1922 première of Renard and asked him, ‘Do you like Beethoven?’

‘I detest him,’ said Stravinsky.

‘But the late quartets?’

‘Worst things he ever wrote.’

He explained later, ‘I should have shared his enthusiasm for Beethoven were it not a commonplace among intellectuals of that time.’

——

It was a Saturday, the day when the Russian choir opposite had its longest and loudest rehearsal. And every time, at the height of a fortissimo, the choir would stop because the sopranos – perhaps due to a mistake in the parts – would make the same mistake. They would move half a tone upwards instead of a whole tone.

Stravinsky had been complaining about the coda of the last movement of the Symphony of Psalms. ‘I simply can’t find an end for the last movement. Every time I think I have found it, it goes wrong and then, pas de pitié, I erase it.’

Suddenly I* heard him come into my studio and put his hands on my shoulders. ‘From where comes this singing?’

‘Oh,’ I said, ‘listen to that Igor Fedorovich. They have been singing the same phrase over and over again for the last fifteen minutes and every time, on the third repeat of the phrase, the sopranos make the same mistake….’

‘Shh… Shhh,’ Stravinsky interrupted and whispered in my ear, ‘be quiet, let me listen’.

‘You see, there it comes again, the mistake.’ But Stravinsky grinned from ear to ear and said, still whispering; ‘But this is beautiful… this is exactly what I need.’ And he ran back to his study.

At half-past-twelve Stravinsky opened my door and exclaimed in a jovial tone: ‘Nika, come on, let’s go and celebrate. We’ll have vodka and caviar. I have found the coda.’

*Nicolas Nabokov (1903-78); Russian-born composer.

——

Relieved at having received his immigration papers and ‘searching about for a vehicle through which I might best express my gratitude, Stravinsky composed a new orchestration for ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ and dedicated it ‘to the American people.’ He knew Congress had made it a civil offence (maximum fine $100) to

embellish or otherwise tamper with the national anthem, but found the existing harmonization (by Damrosch) to be ‘characterless’. After the first performance of his revision on 13 January 1944 in Cambridge, Massachusets, members of the audience filed complaints with the Boston Police Commissioner, Thomas F. Sullivan. At a second concert two nights later, Police Captain Thomas F. Harvey and six members of the ‘radical squad’ attended the performance, preparing to charge Stravinsky with an offence under chapter 264, section 9, of Massachusetts law. ‘Let him change it just once,’ said the captain, ‘and we’ll grab him.’ Warned of the danger, Stravinsky conducted a faultlessly conventional rendition of the anthem. The police did not remain for the rest of the concert.

——

In his first years in Hollywood, Stravinsky badly needed money. The early works, registered in Tsarist Russia, were not protected by copyright and earned him no income; his inter-War compositions were not greatly performed. Eventually, Louis B. Mayer was persuaded to offer him employment.

‘I hear you are the greatest composer in the world,’ said Mayer. Stravinsky bowed.

“Well, this is the greatest movie studio in the world.’ Stravinsky bowed again.

To prove his point, Mayer demonstrated the battery of technological wonders he had installed in his enormous desk.

‘How much will you charge for a music score?’ he finally asked.

‘How long is it?” asked Stravinsky.

‘Say 45 minutes.’

Stravinsky did a mental calculation of the amount of work that had gone into Petrushka and the Rite of Spring, compositions of the desired length, and said ‘$25,000.

‘That’s a lot of money, Mr Stravinsky,’ said Mayer, ‘much more than we normally pay. But since you’re the greatest composer in the world, you shall have it. Now, when can I have the score?’

‘In about one year,’ said Stravinsky.

Mayer stared at him in disbelief. ‘Good day, Mr Stravinsky’, he said.

——

Billy Rose commissioned a piece from Stravinsky for a New York revue, staged in 1945. On the opening night he cabled the composer:’Your music great success stop could be sensational success if you would authorize robert russell bennett retouch orchestration stop bennett orchestrates even the works of cole porter’

Stravinsky replied:

‘SATISFIED WITH GREAT SUCCESS’

[At the opening concert of the 1952 Holland Festival] Stravinsky was presented to Queen Juliana. He was for various reasons, in the foulest of all moods. The Queen, knowing very little about music but wanting to be as friendly as possible, said she was a great admirer of his. Stravinsky said, ‘Which of my works do you specially like?’ The

Queen was nonplussed. There was an interminable moment of silence. Stravinsky began to make a few suggestions, naming works that even Stravinskologists would not remember that he had written.

If she had said ‘yes’ to any of them he would have made a complete fool of her. I*, standing behind Stravinsky, shook my head frantically each time he named a piece. The Queen said, ‘Ah, I don’t think I know that work.’ ‘What about that one?’ he persisted, naming another. I shook my head at her again and contemplated suicide. Then he

relented and said, ‘Petrushka’, and I could at last nod approval.

‘That’s the one,’ said the Queen. The conversation came quickly to an end and Stravinsky trotted off with me, giggling uninhibitedly.

*Peter Diamand (1913-1998), artistic director of the Holland Festival.

——

Rachmaninov and Stravinsky had always spoken disparagingly of each other, so Arthur Rubinstein was astonished when one composer invited him to dinner with the other. Their wives, explained Rachmaninov, had met and become friendly. Conversation proceeded with difficulty at first, Rachmaninov quelling Stravinsky’s social overtures. Then, after a few drinks, Rachmaninov began mocking Stravinsky’s financial problems. ‘Your Petrushka, your Firebird, ha-ha, never earned you a cent of royalties.’ Stravinsky

flushed, then paled. ‘And what about the concertos and the C sharp minor Prelude you published in Russia?’ he responded. ‘You had to play the piano for a living.’ Just as a violent confrontation seemed unavoidable, the two composers sat down amicably and began calculating the fortunes each might have earned if the history of the twentieth century had taken a different course.

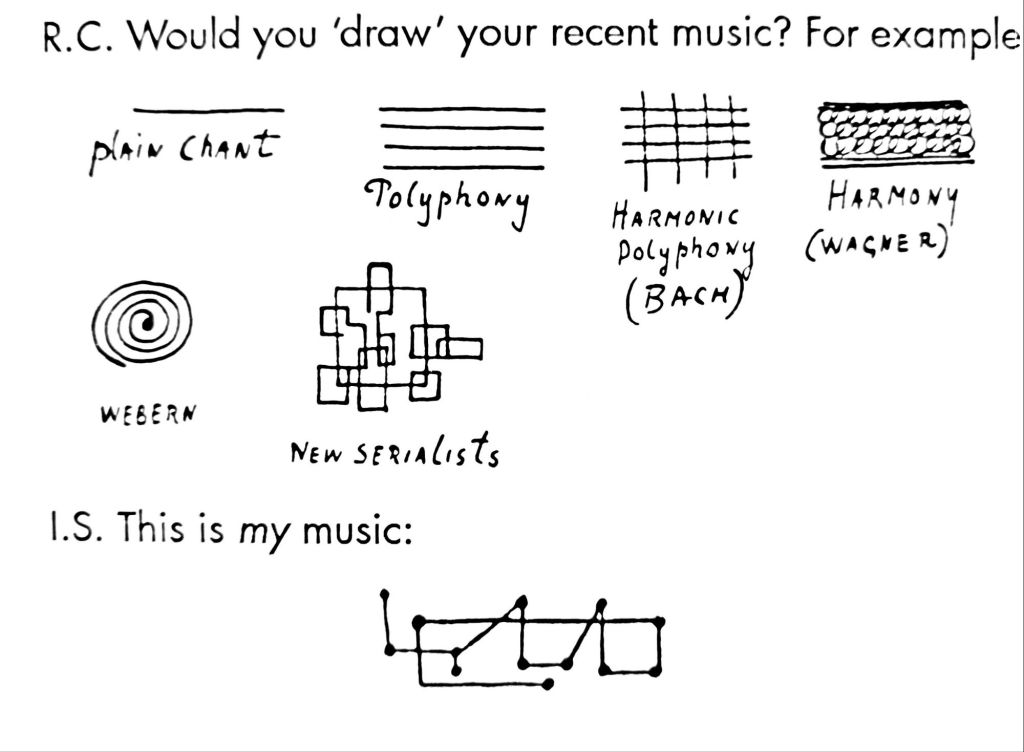

Two excerpt from the first book of interviews (1958) of Igor Stravinsky (I.S.) by Robert Craft (R.C.):

——

R.C. Have you ever thought that music is as Auden says ‘a virtual image of our experience of living as temporal, with its double aspect of recurrence and becoming’?

I.S. If music is to me an ‘image of our experience of living as temporal’ (and however unverifiable, I suppose it is), my saying so is the result of a reflection, and as such is independent of music itself.(…) Auden’s ‘image of our experience of living as

temporal’ is above music, perhaps, but it does not obstruct or contradict the purely musical experience. What shocks me, however, is the discovery that many people think below music. Music is merely something that reminds them of something else-of landscapes, for example; my Apollo is always reminding someone of Greece.

Anecdotes are excerpts from Norman Lebrecht’s “Book of Musical Anecdotes” (1985), and the Interview of Igor Stravinsky by Robert Craft.

Leave a comment