The scientific revolution of the 19th century opened a debate ongoing today: does music answer to universal laws, or not?

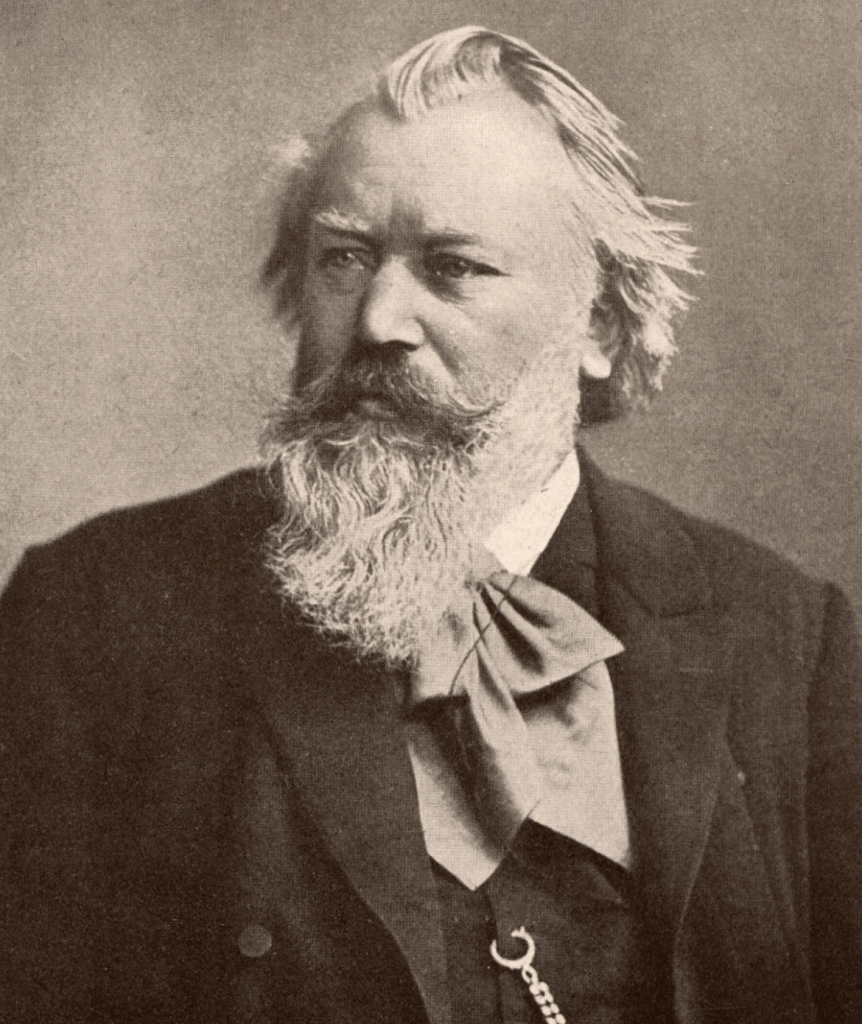

In his time, Johannes Brahms was at the heart of this debate, as told in this short excerpt from his biography by Jan Swafford .

———-

The force of Johannes Brahms’ personality tended to fix young composers in the orbit of his music and his principles. But he considered those creative and technical principles not his own at all. They were the eternal, sacred road of the gods: melody and harmony reined by immutable laws of counterpoint and form.

As Brahms kept faith with those unchanging laws, the world changed around him, and science contributed to that change. Among the epochal studies of the time, which had an abiding influence on music, was the work of Hermann von Helmholtz that established the modern science of acoustics. In his 1862 book On the Sensations of Tone, As a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music, Helmholtz attacked the dogmas of Western musical theory:

At every step we encounter historical and national difference of taste…. What degree of roughness a hearer is inclined to endure as a means of musical expression depends on taste and habit…. Similarly Scales, Modes, and their Modulations have undergone multifarious alterations… hence it follows… that the system of Scales, Modes, and Harmonic Tissues does not rest solely upon inalterable natural laws, but is at least partly also the result of esthetical principles, which have already changed, and will still further change, with the progressive development of humanity.

Helmholtz’s discoveries and their extensions influenced everything from the design of pianos to the international standardization of musical pitch. For composers of coming generations, by challenging the myth of “eternal laws” in music, he not only provided a scientist’s sanction to embrace music of the distant past and of other cultures, but also to explore new territories of harmony and tonality and timbre. The message was unmistakable: if science says that many things are a matter of taste and culture, and taste and culture inevitably evolve, then unheard-of things are possible.

Eager to sound out the views of creative artists, Helmholtz managed to get an interview with Brahms. Their meeting turned out badly. The scientist talked of sine waves and spectra, the composer of counterpoint and form. Helmholtz complained that Brahms and Joachim* “always give me artistic musical answers to my questions regarding scientific acoustical problems!” Brahms responded: “In musical things, he is an enormous dilettante.” Billroth’s passion for Helmholtz** Brahms wrote off as more dilettantism.

The Scales, Modes, and Harmonic Tissues the scientist and the physician saw as conditional, time-bound cultural constructs, Brahms saw simply as what music was about. To his mind, the dissolution of the assumptions and procedures of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven was not a matter of the “progressive development” of art and humanity, but rather a sign of the decline of art and humanity. In the profoundest sense, Brahms and Helmholtz spoke different languages: one a language of the past, the other of a future that stretched all the way to the advent of electronic music nearly a century later.

From: Johannes Brahms, a biography, Jan Swafford, page 509

*Joseph Joachim was a Hungarian violinist and composer, close collaborator of Johannes Brahms. he is widely regarded as one of the most distinguished violinists of the 19th century.

**Theodor Billroth was a German surgeon and amateur musician. As a surgeon, he is generally regarded as the founding father of modern abdominal surgery. As a musician, he was a close friend and confidant of Johannes Brahms.

———-

Leave a comment