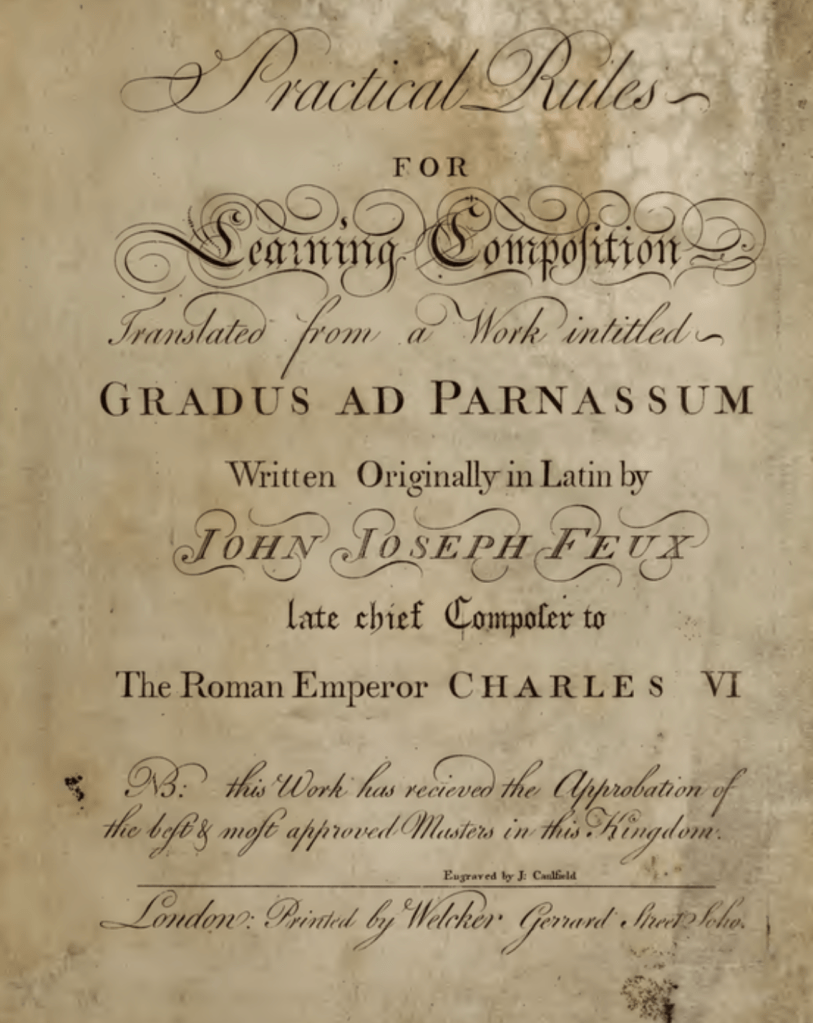

This week-end, the UP CLOSE AND CLASSICAL concerts will feature Mozart’s string quartet #19 which was nicknamed “Dissonance”. But what is dissonance? In the 18th century, there was an easy answer. Harmony followed rules recently inherited from vocal music, and consigned in authoritative teachings like Joseph Fux’s “Gradus ad Parnassum”. Most 18th century’s ears were trained as singers’ ears: certain proportions in sound provided pleasure, and the mathematic rules defining consonance and dissonance were identical for all. This definition still applies when listening to Mozart’s music today.

Unison, third, fifth, sixth, octave, and the intervals made up of these and the octave are consonances. Some of these are perfect consonances, the others imperfect. The unison, fifth, and octave are perfect*. The sixth and third are imperfect. The remaining intervals, like the second, fourth,’ diminished fifth, tritone, seventh, and the intervals made up of these and the octave, are dissonances.

These are the elements which account for all harmony in music. The purpose of harmony is to give pleasure. Pleasure is awakened by variety of sounds. This variety is the result of progression from one interval to another, and progression, finally, is achiered by motion. Thus it remains to examine the nature of motion. Motion in music denotes the distance covered in passing from one interval to another in either direction, up or down.

Joseph Fux, Gradus ad Parnassum (1725) Part I – Musica Speculativa

(* These unison, fifth and octave “perfect” intervals correspond to proportionalities of 1:1, 3:2 and 2:1)

By 1939, at the time when Igor Strawinsky wrote his Poetics of Music, the definition of “consonance” and “dissonance” had changed for composers and music listeners, but that it was still perceived as an “element of transition” by most audiences.

The concepts of consonance and dissonance have given rise to tendentious interpretations that should definitely be set aright.

Consonance, says the dictionary, is the combination of several tones into an harmonic unit. Dissonance results from the deranging of this harmony by the addition of tones foreign to it. One must admit that all this is not clear. Ever since it appeared in our vocabulary, the word dissonance has carried with it a certain odor of sinfulness.

Let us light our lantern: in textbook language, dissonance is an element of transition, a complex or interval of tones which is not complete in itself and which must be resolved to the ear’s satisfaction into a perfect consonance.

But just as the eye completes the lines of a drawing which the painter has knowingly left incomplete, just so the ear may be called upon to complete a chord and cooperate in its resolution, which has not actually been realized in the work. Dissonance, in this instance, plays the part of an allusion.

Either case applies to a style where the use of dissonance demands the necessity of a resolution. But nothing forces us to be looking constantly for satisfaction that resides only in repose. And for over a century music has provided repeated examples of a style in which dissonance has emancipated itself. It is no longer tied down to its former function. Having become an entity in itself, it frequently happens that dissonance neither prepares nor anticipates anything. Dissonance is thus no more an agent of disorder than consonance is a guarantee of security. The music of yesterday and of today unhesitatingly unites parallel dissonant chords that thereby lose their functional value, and our ear quite naturally accepts their juxtaposition.Of course, the instruction and education of the public have not kept pace with the evolution of technique. The use of dissonance, for ears ill-prepared to accept it, has not failed to confuse their reaction, bringing about a state of debility in which the dissonant is no longer distinguished from the consonant.

We thus no longer find ourselves in the framework of classic tonality in the scholastic sense of the word. It is not we who have created this state of affairs, and it is not our fault if we find ourselves confronted with a new logic of music that would have appeared unthinkable to the masters of the past. And this new logic has opened our eyes to riches whose existence we never suspected.

Having reached this point, it is no less indispensable to obey, not new idols, but the eternal necessity of affirming the axis of our music and to recognize the existence of certain highlighters poles of attraction. Diatonic tonality is only one means of orienting music towards these poles. The function of tonality is completely subordinated to the force of attraction of the pole of sonority. All music is nothing more than a succession of impulses that converge towards a definite point of repose. That is as true of Gregorian chant as it is of a Bach fugue, as true of Brahms’s music as it is of Debussy’s.Igor Strawinsky (1885-1970) The Poetics of Music

Leave a comment