The lives of three of the composers featured on our February 1st-2nd concerts were deeply affected by the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany, World War II and their emigration. They would likely have been more famous as composers if war had not happened, but all three left a deep mark in 20th century music.

Careers in Austria, Germany and Switzerland before World War II

Adolf Busch (1891-1952) studied at the Cologne Conservatory. In 1912, Busch founded the Vienna Konzertverein Quartet, consisting of the principals from the Konzertverein orchestra, which made its debut at the 1913 Salzburg Festival. After World War I, he founded the Busch Quartet. The quartet was in existence with varying personnel until 1951. The additional member of the circle was Rudolf Serkin, who became Busch’s duo partner at 18 and eventually married Busch’s daughter, Irene, 1935 in Basel. The Busch Quartet and Serkin became the nucleus of the Busch Chamber Players, founded in Basel, a forerunner of modern chamber orchestras.

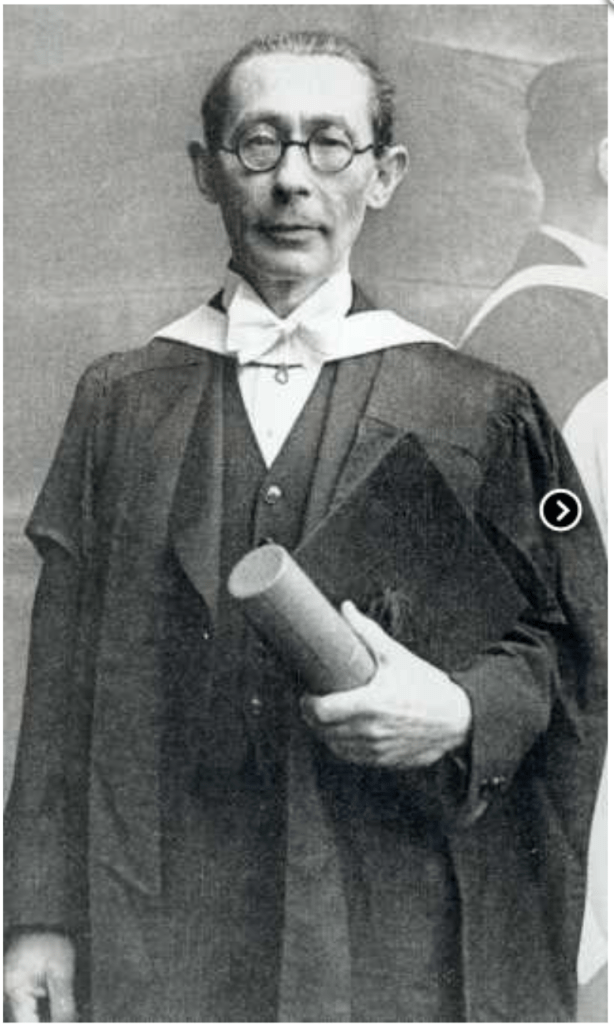

Hans Gál (1890–1987) grew up in Vienna, Austria. Gál obtained his music-teaching certificate, which included music history, piano-playing and harmony, under Richard Robert’s supervision in 1909. Georg Szell, Hans, Rudolf Serkin, Rudolf Schwarz and many other musicians studied with Robert. Through Robert, Gál met his mentor and ‘spiritual father’ in Eusebius Mandyczewski(1857-1929), who had belonged to Brahms’s closest circle of friends, and under whom Gál worked intensively for two years (1909-11) on musical form and counterpoint. By the second half of the 1920s Hans Gál was a successful composer of piano, chamber, choral and orchestral works. His opera “Die Heilige Ente” was performed all over Germany. He also wrote, with Mandyczewski, the first Complete Edition of the works of Brahms. In 1929, with the support of famous conductors Wilhelm Fürtwangler, Fritz Busch (Adolf’s brother) and Richard Strauss, he became the director of the conservatory of Mainz, in the Rhineland, overseeing a thousand students and seventy teachers.

Ingolf Dahl (1912-1970) was born Walter Ingolf Marcus in Hamburg, Germany, to a German Jewish father, attorney Paul Marcus, and his Swedish wife Hilda Maria Dahl.

In Hamburg, Dahl studied piano under Edith Weiss-Mann, a harpsichordist, pianist, and a proponent of early music. Dahl studied with Philipp Jarnach at the Hochschule für Musik Köln (1930–32).

Fleeing the nazi regime

In 1927, with the rise of Adolf Hitler, Adolf Busch decided he could not in good conscience stay in Germany, so he emigrated to Basel, Switzerland. Busch was not Jewish and was popular in Germany, but firmly opposed Nazism from the beginning. On 1 April 1933, he repudiated Germany altogether and in 1938, he boycotted Italy. As the Nazis tried to convince him to return to Germany, he declared that he would “return with joy on the day that Hitler, Goebbels und Göring are publicly hanged.” In 1935, he became a Swiss citizen of Riehen, Basel.

The National Socialists occupied Mainz in March 1933 – the city was in no way a Nazi hotbed, and in fact a detachment had to be sent from Worms to achieve this – , hoisting the swastika on public buildings, including the Conservatory, and articles soon appeared in the local press denouncing ‘the Jewish control’ of the conservatory – one concluded with the words ‘Away with the Jew Gál. Mainz Conservatory for German Art!’. On 29th March Hans Gál received a letter from the authorities with the brief communication: ‘I hereby suspend you with immediate effect.’ His secretary recalled that ‘Director Gál just picked up his hat and went’. But it was not only his employment that was lost; all performances and publication of his works were henceforth forbidden in Germany, depriving him at a stroke of his livelihood. At first Gál protested vehemently against his dismissal, invoking – in vain – a clause in the law which exempted from dismissal those ‘non-Arians’ “who had fought at the front for the German Reich or for its allies in the World War”. He was reluctant to believe that this situation could last. Shortly after Hitler had become Chancellor, Gál had attended a concert on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Wagner’s death at which Hitler was also present, sitting near him. Gál had looked carefully at Hitler’s face and concluded that no-one could possibly take him seriously. Events proved him tragically wrong. The Gáls returned to Vienna. But Austria was, in fact, far from the ideal place for exiles from Nazi oppression in Germany. Even before the annexation in 1938 it became increasing evident that there was no future for the Gáls in Austria. When Hitler invaded, ‘annexing’ Austria to the ‘Third Reich’, it was clear that there was no alternative to flight, especially as the Austrian population welcomed Hitler with open arms. Shortly after the German troops crossing the border Gál and his family made their way to London, with the intention of emigrating to America. He then moved to Edinburgh, where he was arrested on Whit Sunday, in May, 1940, and moved to Douglas, on the Isle of Man. The experience was far from pleasant, with total powerlessness in the face of mindless and petty bureaucracy, that appeared not to have understood the difference between Nazis and ‘refugees from Nazi oppression’. By the autumn of 1940, as a result of lobbying by liberally-minded politicians and other figures, and also in the light of the sinking of the Arandora Star, the folly of the internment policy was realised. Gál was able to return to Edinburgh in late September of that year, a free man.

Ingolf Dahl left Germany as the Nazi Party was coming to power in 1933 and continued his studies at the University of Zurich. Living with relatives and working at the Zürich Opera for more than six years, he rose from an internship to the rank of assistant conductor. He served as a vocal coach and chorus master for the world premieres of Alban Berg’s Lulu and Paul Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler. Since Switzerland became increasingly hostile towards Jewish refugees and Dahl’s role at the Opera was restricted to playing in the orchestra, he emigrated to the United States in 1939.

Careers after emigration to Vermont, Edinburgh and Los Angeles

During 12 years in Basel and besides his many concerts around the world, Adolf Busch founded a chamber orchestra in Basel, was a co-founder of the Lucerne Festival in 1938, together with Arturo Toscanini and his conducting brother Fritz Busch, and taught many students in Basel, among them Yehudi Menuhin. On the outbreak of World War II, Busch emigrated from Basel to the United States in 1939, where he eventually settled in Vermont. There, he was one of the founders with Rudolf Serkin of the Marlboro Music School and Festival.

The Busch Quartet was particularly admired for its interpretations of Brahms, Schubert, and above all Beethoven. As a composer, Busch was influenced by Max Reger. He was among the first to compose a Concerto for Orchestra, in 1929. A number of his compositions have been recorded, including the Violin Concerto (A minor, opus 20, published 1922), String Sextet (G major, opus 40), Quintet for Saxophone and String Quartet, Violin Sonata No 2, Op. 56, Clarinet Sonata, and several large scale works for organ. Regarding the last, Busch once remarked that if he could come back after his death he would like to return as an organist.

He was the son of the luthier Wilhelm Busch; brother of the conductor Fritz Busch, the cellist Hermann Busch, the pianist Heinrich Busch and the actor Willi Busch, father in law of the pianist Rudolf Serkin and maternal grandfather of the pianist Peter Serkin and the cellist Judith Serkin. An exhaustive two-volume biography of Busch by Tully Potter was published in 2010 by Toccata Press In November 2015, Warner Classics released a 16-CD collection of Busch’s recordings of Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, and other composers.

After internment Hans Gál returned to Edinburgh. But without employment, accommodation or source of income the prospects were not promising. With the end of the war the situation for the Gáls began to improve markedly. First, the new Professor of Music at Edinburgh University, Sydney Newman, obtained for him a permanent teaching post in the music faculty, providing financial security and a focus for his activities. He remained active at the university well beyond retirement age, and resided in Edinburgh until the end of his life. He became a well-known personality in the musical life of the city, as composer, performer, scholar and teacher. Gál’s musical roots were still firmly anchored in the Austro-German tradition, and he never became part of the cultural establishment in his adopted homeland. As early as 1948 he returned to Vienna to take part in a performance. In the same year he went back to Germany for the first performance of his De Profundis and again in 1956 for that of Lebenskreise, commissioned by the Mainz Choir on the occasion of their 125th anniversary. In 1958 he was awarded the Austrian State Prize, and with the money he and his family spent their first post-war holiday in Austria. Gál was (and remains to this day) probably better known through his activities as scholar and writer than through his music. Over the years he wrote a number of books, which brought him wide recognition and success. In the early 1960s Gál wrote monographs on Brahms (1961) and Wagner (1963). These are not dry scholarly tomes but spring from intimate knowledge of the composers works. As a friend and close collaborator of Mandyczewski, and co-editor of the complete edition of Brahms’s works, he had a deep affinity with Brahms, enabling him to penetrate into both works and personality. With Wagner, he attempted to steer a middle way between the greatness of his music and the monstrosity of his ideology. The great value of both works is that they are written from the perspective of the practising musician rather than the mere scholar. In the 1970s Gál wrote two more monographs: on Schubert (1970) and Verdi (1975). A deep love of Schubert’s music permeates the former work, while in the latter Gál’s own experiences as a successful opera composer no doubt contribute to his understanding of the dramatic and literary, as well as the musical aspects of Verdi’s work. A characteristic of Gál’s music is its remarkable consistency and originality of style. Though deeply rooted in the Austro-German musical tradition, he had by his early twenties already found his own musical language, to which, though always open to new forms and combinations, he remained faithful. Hans Gál died of cancer on 3rd October, 1987, at the age of 97.

Photos: 1952 USC Composition faculty with Dahl on the right. Dahl and Stravinsky chat in the 1960’s

Ingolf Dahl settled in Los Angeles and joined the community of expatriate musicians that included Ernst Krenek, Darius Milhaud, Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, and Ernst Toch. He had a varied musical career as a solo pianist, keyboard performer (piano and harpsichord), accompanist, conductor, coach, composer, and critic. He produced a performing translation of Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire in English and translated, either alone or with a collaborator, such works as Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music. He performed many of Stravinsky’s works and the composer was impressed enough to contract Dahl to create a two-piano version of his Danses concertantes and program notes for other works. In 1945 he joined the faculty of the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music in Los Angeles, where he taught for the rest of his life. In 1952 he was appointed the first head of the Tanglewood Study Group, a program that targeted not professionals but “the intelligent amateur and music enthusiast, also the general music student and music educator”. In 1957 he co-directed the Ojai Music Festival in partnership with Aaron Copland and served as its music director from 1964 to 1966. He died in Frutigen, Switzerland, on August 6, 1970, just a few weeks after the death of his wife on June 10. Among Dahl’s students are the American conductors Michael Tilson Thomas, Lawrence Christianson, William Hall, William Dehning, Frank A. Salazar, the pianist William Teaford, and the composers Morten Lauridsen, Williametta Spencer, Norma Wendelburg, and Lawrence Moss. Tilson Thomas assessed him this way: “Dahl was an inspiring teacher; over and above the subject matter, he showed his students about the practical value of humanism. That is, how to let humanistic concerns infuse your daily existence.”

Leave a comment