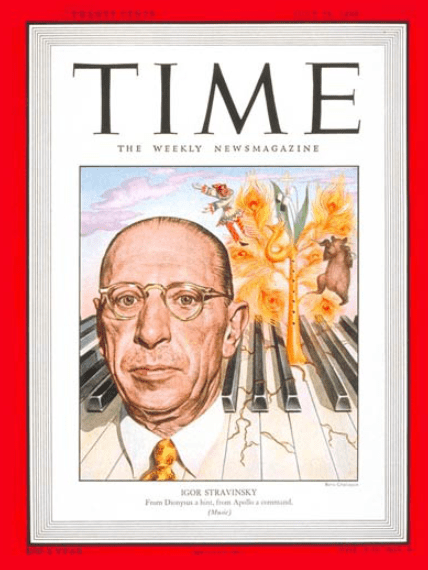

Born in Hamburg, Germany to Swedish parents, Ingolf Dahl (1912-1970) began his formal music education in Cologne in 1930. Fearing the oppression of the Nazi party coming to power, he fled to Switzerland and continued his studies at the University of Zürich. Dahl’s first professional assignment out of school was as conductor and coach for the Zürich Stadttheater. In 1938, Dahl emigrated to the United States and settled in Los Angeles, where he worked as a composer and conductor for radio and film, gave lectures and piano recitals, and attended master classes with Nadia Boulanger. He became a naturalized citizen of the US in 1943, and two years later joined the faculty of the University of Southern California (USC), where he taught until his death. As conductor of the university’s symphony orchestra, Dahl gave West Coast premieres of a wide variety of contemporary works from the US and Europe. His close collaboration with Igor Stravinsky had a significant effect on Dahl’s own work, leading him to lecture, perform, and arrange Stravinsky’s music as well as translate his Poetics of Music (1947).

Below are short excerpts of each of the six chapters (lessons) of Igor Stravinsky’s “Poetics of Music”, as well as an excerpt of the epilogue.

1- Getting acquainted

We cannot observe the creative phenomenon independently of the form in which it is made manifest. Every formal process proceeds from a principle, and the study of this principle requires precisely what we call dogma. In other words, the need that we feel to bring order out of chaos, to extricate the straight line of our operation from the tangle of possibilities and from the indecision of vague thoughts, presupposes the necessity of some sort of dogmatism. I use the words dogma and dogmatic, then, only insofar as they designate an element essential to safeguarding the integrity of art and mind, and I maintain that in this context they do not usurp their function.

The very fact that we have recourse to what we call order that order which permits us to dogmatize in the field we are considering – not only develops our taste for dogmatism: it incites us to place our own creative activity under the aegis of dogmatism. That is why I should like to see you accept the term.

2- The phenomenon of music

For myself, I cannot begin to take an interest in the phenomenon of music except insofar as it emanates from the integral man. I mean from a man armed with the resources of his senses, his psychological faculties, and his intellectual equipment.

Only the integral man is capable of the effort of higher speculation that must now occupy our attention.

For the phenomenon of music is nothing other than a phenomenon of speculation. There is nothing in this expression that should frighten you. It simply presupposes that the basis of musical creation is a preliminary feeling out, a will moving first in an abstract realm with the object of giving shape to something concrete. The elements at which this speculation necessarily aims are those of sound and time. Music is inconceivable apart from those two elements.(…)Mr. Souvtchinsky thus presents us with two kinds of music: one which evolves parallel to the process of ontological time, embracing and penetrating it, inducing in the mind of the listener a feeling of euphoria and, so to speak, of “dynamic calm.”

The other kind runs ahead of, or counter to, this process. It is not self-contained in each momentary tonal unit. It dislocates the centers of attraction and gravity and sets itself up in the unstable; and this fact makes it particularly adaptable to the translation of the composer’s emotive impulses. All music in which the will to expression is dominant belongs to the second type.

This problem of time in the art of music is of capital importance.

3- The composition of music

This premonition of an obligation, this foretaste of a pleasure, this conditioned reflex, as a modern physiologist would say, shows clearly that it is the idea of discovery and hard work that attracts me.

The very act of putting my work on paper, of, as we say, kneading the dough, is for me inseparable from the pleasure of creation. So far as I am concerned, I cannot separate the spiritual effort from the psychological and physical effort; they confront me on the same level and do not present a hierarchy.

The word artist which, as it is most generally understood today, bestows on its bearer the highest intellectual prestige, the privilege of being accepted as a pure mind this pretentious term is in my view entirely incompatible with the role of the

“homo faber”.At this point it should be remembered that, whatever field of endeavor has fallen to our lot, if it is true that we are intellectuals, we are called upon not to cogitate, but to perform. The philosopher Jacques Maritain reminds us that in the mighty structure of medieval civilization, the artist held only the rank of an artisan.

“And his individualism was forbidden any sort of anarchic development, because a natural social discipline imposed certain limitative conditions upon him from without.” It was the Renaissance that invented the artist, distinguished him from the artisan and began to exalt the former at the expense of the latter.

At the outset the name artist was given only to the Masters of Arts: philosophers, alchemists, magicians; but painters, sculptors, musicians, and poets had the right to be qualified only as artisans.

4- Musical typology

It just so happens that our contemporary epoch offers us the example of a musical culture that is day by day losing the sense of continuity and the taste for a common language.

Individual caprice and intellectual anarchy, which tend to control the world in which we live, isolate the artist from his fellow-artists and condemn him to appear as a monster in the eyes of the public; a monster of originality, inventor of his own language, of his own vocabulary, and of the apparatus of his art. The use of already employed materials and of established forms is usually forbidden him. So he comes to the point of speaking an idiom without relation to the world that listens to him. His art becomes truly unique, in the sense that it is incommunicable and shut off on every side. The erratic block is no longer a curiosity that is an exception; it is the sole model offered neophytes for emulation. The appearance of a series of anarchic, incompatible, and contradictory tendencies in the field of history corresponds to this complete break in tradition. Times have changed since the day when Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi quite evidently spoke the same language which their disciples repeated after them, each one unwittingly transforming this language according to his own personality. The day when Haydn, Mozart, and Cimarosa echoed each other in works that served their successors as models, successors such as Rossini, who was fond of repeating in so touching a way that Mozart had been the delight of his youth, the desperation of his maturity, and the consolation of his old age.Those times have given way to a new age that seeks to reduce everything to uniformity in the realm of matter while it tends to shatter all universality in the realm of the spirit in deference to an anarchic individualism. That is how once universal centers of culture have become isolated. They withdraw into a national, even regional, framework which in its turn splits up to the point of eventual disappearance. Whether he wills it or not, the contemporary artist is caught in this infernal machination. There are simple souls who rejoice in this state of affairs. There are criminals who approve of it. Only a few are horrified at a solitude that obliges them to turn in upon themselves when everything invites them to participate in social life.

The universality whose benefits we are gradually losing is an entirely different thing from the cosmopolitanism that is beginning to take hold of us. Universality presupposes the fecundity of a culture that is spread and communicated everywhere, whereas cosmopolitanism provides for neither action nor doctrine and induces the indifferent passivity of a sterile eclecticism. Universality necessarily stipulates submission to an established order. And its reasons for this stipulation are convincing. We submit to this order out of sympathy or prudence. In either case the benefits of submission are not long in appearing.

5- The avatars of Russian music.

At the same time, it is noteworthy that the clearly political interests that are constantly brought to bear on musical folklore should go hand in hand, as is always the case in Russia, with a confused and complicated theory expressly pointing out that “the different regional cultures are evolving and broadening into a musical culture of the whole great socialist country.”

Here is what one of the most outstanding of Soviet music critics and musicologists writes: “It is high time that we abandon the distinction entirely feudal, bourgeois, and pretentious between folk music and artistic music. As if the quality of being aesthetic were only the privilege of the individual invention and personal creation of the composer.”If the growing interest in musical ethnography is bought at the price of such heresies, it would perhaps be preferable that this interest be exercised on the pre-revolutionary primitive musical forms, otherwise it runs the risk of bringing only harm and confusion to Russian music.

6- The performance of music.

It is necessary to distinguish two moments, or rather two states of music: potential music and actual music. Having been fixed on paper or retained in the memory, music exists already prior to its actual performance, differing in this respect from all the other arts, just as it differs from them, as we have seen, in the categories that determine its perception.

The musical entity thus presents the remarkable singularity of embodying two aspects, of existing successively and distinctly in two forms separated from each other by the hiatus of silence. This peculiar nature of music determines its very life as well as its repercussions in the social world, since it presupposes two kinds of musicians: the creator and the performer. (…)To speak of an interpreter means to speak of a translator. And it is not without reason that a well-known Italian proverb, which takes the form of a play on words, equates translation with betrayal.

Conductors, singers, pianists, all virtuosos should know or recall that the first condition that must be fulfilled by anyone who aspires to the imposing title of interpreter, is that he be first of all a flawless executant. The secret of perfection lies above all in his consciousness of the law imposed upon him by the work he is performing. And here we are back at the great principle of submission that we have so often invoked in the course of our lessons. This submission demands a flexibility that itself requires, along with technical mastery, a sense of tradition and, commanding the whole, an aristocratic culture that is not merely a question of acquired learning.

This submissiveness and culture that we require of the creator, we should quite justly and naturally require of the interpreter as well. Both will find therein freedom in extreme rigor and, in the final analysis, if not in the first instance, success – true success, the legitimate reward of the interpreters who in the expression of their most brilliant virtuosity preserve that modesty of movement and that sobriety of expression that is the mark of thoroughbred artists.

Epilogue

In truth, there is no confusion possible between the monotony born of a lack of variety and the unity which is a harmony of varieties, an ordering of the Many.

“Music,” says the Chinese sage Seu-ma-tsen in his memoirs, “is what unifies.” This bond of unity is never achieved without searching and hardship.But the need to create must clear away all obstacles. I think at this point of the gospel parable of the woman in travail who “hath sorrow, because her hour is come: but as soon as she is delivered of the child, she remembereth no more the anguish, for joy that a man is born into the world.” How are we to keep from succumbing to the irresistible need of sharing with our fellow men this joy that we feel when we see come to light something that has taken form through our own action?

For the unity of the work has a resonance all its own. Its echo, caught by our soul, sounds nearer and nearer. Thus the consummated work spreads abroad to be communicated and finally flows back towards its source. The cycle, then, is closed. And that is how music comes to reveal itself as a form of communion with our fellow man and with the Supreme Being.

Leave a comment