Our next concert will feature Francis Poulenc’s Trio for oboe, piano and bassoon (or cello), premiered in 1928.

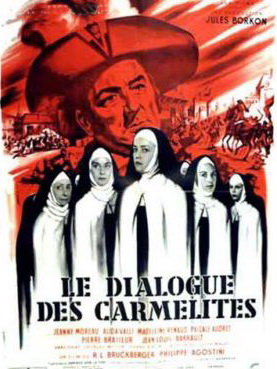

Francis Poulenc (1899 – 1963) was a French composer and pianist. His compositions include songs, solo piano works, chamber music, choral pieces, operas, ballets, and orchestral concert music. Among the best-known are the piano suite Trois mouvements perpétuels (1919), the ballet Les biches (1923), the Concert champêtre (1928) for harpsichord and orchestra, the Organ Concerto (1938), the opera Dialogues des Carmélites (1957), and the Gloria (1959) for soprano, choir, and orchestra.

As the only son of a prosperous manufacturer, Poulenc was expected to follow his father into the family firm, and he was not allowed to enrol at a music college. He studied with the pianist Ricardo Viñes, who became his mentor after the composer’s parents died. Poulenc also made the acquaintance of Erik Satie, under whose tutelage he became one of a group of young composers known collectively as Les Six. In his early works Poulenc became known for his high spirits and irreverence. During the 1930s a much more serious side to his nature emerged, particularly in the religious music he composed from 1936 onwards, which he alternated with his more light-hearted works.

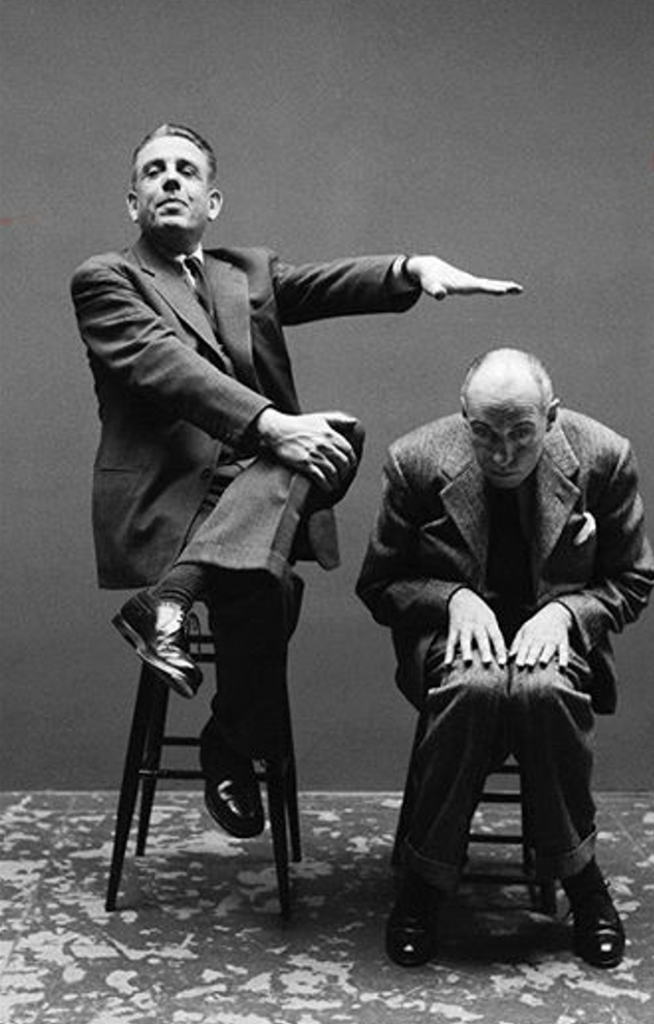

In addition to his work as a composer, Poulenc was an accomplished pianist. He was particularly celebrated for his performing partnerships with the baritone Pierre Bernac and the soprano Denise Duval. He toured in Europe and America with both of them, and made a number of recordings as a pianist. He was among the first composers to see the importance of the gramophone, and he recorded extensively from 1928 onwards.

In his later years, and for decades after his death, Poulenc had a reputation, particularly in his native country, as a humorous, lightweight composer, and his religious music was often overlooked. In the 21st century, more attention has been given to his serious works, with many new productions of Dialogues des Carmélites and La voix humaine worldwide, and numerous live and recorded performances of his songs and choral music.

Going beyond the above introduction from Wikipedia, reveals the inner tensions that were part of Poulenc’s life:

- Despite his early “irreverence” and gaps in academic training, Poulenc wanted to be remembered as a serious composer.

- Poulenc was one of the first famous composers to be open about his homosexuality, yet his most enduring success is in the standard repertoire of opera houses, with the deeply religious opera “Dialogues of the Carmelites”.

Excerpts from Poulenc’s biography by Roger Nichols:

Poulenc preferred accompanied tunes and juxtapositions; in place of pathos (‘music to be listened to head in hands’, as Cocteau described it), charm and delight; in place of textures that swamp the listener, primary colours with plenty of space around them.

The French have never bought into the ancient British cult of the talented amateur. Art, like business, is a serious matter and, as evidenced by both sides of Poulenc’s family, one needs to be properly trained. Viñes’s teaching had obviously been vital, and Poulenc had also benefited from lessons given from time to time by other helpful musical friends, but this did not constitute a teaching programme comparable with that of the Conservatoire or the Schola Cantorum.

Six bars on the autograph of Rapsodie nègre may be the remains of this piece, which otherwise has vanished, but we do learn that Poulenc’s habit of composing at the piano was already established – any qualms he might have had about this were eased by remembering Rimsky-Korsakov’s advice to Stravinsky: ‘Some composers compose away from the piano, some at the piano: you compose at the piano.’

(…)which was to be the first of his great successes: the Trois Mouvements perpétuels for piano.(…)

The great pianist Alfred Cortot, writing in 1930, had the measure of Poulenc’s achievement in these three pieces: . . . acclaimed by virtuosos as well as by amateurs with a welcome that was as justified as it was immediate, and which resolve the delicate problem of instantly adapting the ironically subversive aspects of Satie’s technique to the easily outraged taste of middle-of-the-road salons. There is nothing, in fact, in these three amiable pieces, clearly inspired by the manner of the composer of the Gymnopédies, which does not lend itself to delightful listening, and equally to a calm and contented spirit. There is no dissonance, however fleeting, that does not find itself clothed in the attractiveness of an engaging melodic idea; no daring passage, even if it is concealed, which does not recover through a charming display of goodheartedness.

One of the most remarkable aspects of these extraordinary pieces is indeed the self-effacement of the composer, mirrored in his warning ‘Pianists must forget they are virtuosos’ – not a million miles from Debussy’s already quoted adjuration to those taking the solo roles in Pelléas et Mélisande to ‘forget you are singers’.

The sticking point for both Poulenc and Auric was the introduction of Satie’s musique d’ameublement, or ‘furniture music’. The first page of Satie’s autograph explains that this ‘replaces “waltzes” and “operatic fantasias” etc. Don’t be confused! It’s something else!!! No more “false music” . . . Furniture music completes one’s property; . . . it’s new; it doesn’t upset customs; it isn’t tiring; it’s French; it won’t wear out; it isn’t boring.’43 Turning his back on the whole notion of a work of art, sneeringly designated an ‘oeuvre’, Satie wanted the music to be ignored, like furniture and, when the audience obviously started to pay attention, was driven to shouting ‘Go on talking! Walk about! Don’t listen!’ . . . to no avail. Had he foreseen the ‘muzak’ of the future, maybe he might have embraced Poulenc’s and Auric’s scepticism.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the divided self is a prime creator of misery and self-doubt. The gulf between the jollity of the general’s polka on one hand and on the other the gritty dissonances of the Quatre Poèmes de Max Jacob, and also of the ten Promenades for piano, written for Arthur Rubinstein during the summer of 1921 (and barely spoken of again by Poulenc), might have caused even the most experienced composer to halt and take stock, even if the purposes of the two styles were acknowledged as being widely disparate.

In December 1921 Vincent d’Indy, as a visiting professor, complained that ‘the pupils at the University of Montreal are in too much of a hurry and want to learn about the whole of music in 3 months and don’t produce anything except what follows the gospel of Poulenc and Darius Milhaud. This tendency needs to be checked and they should be taught the real meaning of Art.’ (…) Clearly Poulenc was now in need of some wise advice.

His lessons with Koechlin, fifty-eight in all, lasted from November 1921 to March 1925. At the end of his life, Poulenc expressed his gratitude for Koechlin’s openness to his pupils’ character: ‘Having felt, as a result, that like most Latins I was more of a harmonist than a contrapuntist, he made me write four-part realizations of Bach chorale themes as well as the usual counterpoint exercises

Les Biches marked Poulenc’s first major and almost unanimous success. Over the next four years it was danced in thirteen major European cities to similar acclaim, so perhaps the most surprising thing is that, as far as we know, in the five years left to him Diaghilev never spoke about commissioning a sequel.

In the whole of 1924 Poulenc, (…) began only two new works: in May the Trio for oboe, bassoon and piano, which would take him two years to finish;

His most observant comment came in 1958: ‘I’m not suited to poetry on classical lines. Each time I’ve tried it, for example in the Cinq Poèmes de Ronsard, it hasn’t been a success.’ This was also the advice from his friend Auric, who urged him to ‘stay with Apollinaire, set Max Jacob, Éluard and Reverdy’, and Poulenc spoke of Picasso’s cover as being, without question, the best thing about the work.

Poulenc commenting with the slightest edge of bitterness that ‘For the first time in a review of my music I read the words “magnifique, très émouvant” [“magnificent, very moving”] for the fourth song (“Je n’ai plus que les os”) – I’m slightly surprised to find these adjectives replacing “charmant, délicieux” [“charming, delightful”]. I didn’t think I’d made such a major breakthrough.’

One of the ‘must-hear’ occasions of 1926 Paris, after the city’s premiere of Ravel’s L’Enfant et les sortilèges on 1 February, was the Auric/Poulenc concert in the Salle des Agriculteurs on 2 May, containing six works by Auric, including two first performances, and four by Poulenc: a repeat of Poèmes de Ronsard and first performances of the Trio for oboe, bassoon and piano, Napoli played by Marcelle Meyer, and the Chansons gaillardes sung by a baritone introduced to Poulenc after he had been searching a long time.

Between these two premieres, however, was another that was to have a far deeper and more lasting influence on him: on 30 May Stravinsky conducted Oedipus Rex. That morning, after attending the dress rehearsal the previous evening, Poulenc wrote to the composer: Dear Stravinsky, I couldn’t find anything to say to you yesterday evening that precisely expresses my enthusiasm. I feel that this evening it will be the same thing. Even so I do want you to know into what a state of superior emotion you plunged me yesterday. Your art has risen to such a height that it would need the language of Sophocles himself to speak of it. My God, it’s so beautiful! Permit me to embrace you. It is a rare honour for me. Your faithful Poulenc.

(…)

Performances were rare in the next two decades [. . .]’ So Poulenc’s enthusiasm was going very much against the general trend. Secondly, in asking what it was he found that eluded others, we are to some extent helped by his underlining of the word ‘supérieure’ and the possibility it offers that the work tapped into some kind of religious feeling. But Stravinsky pointedly asked, ‘In what sense is the music religious? I do not know how to answer because the word does not correspond in my mind to a state of feeling or sentiment, but to dogmatic beliefs’ – a position closely connected to the fact that ‘the music was composed during my strictest and most earnest period of Christian Orthodoxy’. We may nonetheless agree with Stephen Walsh in admiring the work’s ‘extraordinary spiritual grandeur’ and even tie this up, tendentiously, with Stravinsky’s admission that ‘I do, of course, believe in a system beyond Nature’. But whether or not some residue of religious feeling remained with Poulenc during the 1920s and early 1930s, there can be little doubt that Oedipus also taught him lessons in musical technique. A further quotation from Stravinsky about the work is relevant: ‘My audience is not indifferent to the fate of the person, but I think it far more concerned with the person of the fate, and the delineation of it which can be achieved uniquely in music . . . Crossroads are not personal but geometrical, and the geometry of tragedy, the inevitable intersecting of lines, is what concerned me.’

IV DEPRESSION AND RECOVERY 1929–1934

(…) In the meantime, in February Poulenc had happened to see in the street a young man he knew slightly called Richard Chanlaire, a talented painter and amateur violinist. They got talking and Poulenc felt Chanlaire was sympathetic enough to listen to his woes. Shortly afterwards he sent him several phonograph records by way of thanks for his friendship, offered ‘at the bottom of his abyss’, and invited him to come and listen to Ansermet conducting Les Noces on 24 February. Suddenly, and it seems quite unexpectedly, Poulenc found himself in love. Lacombe describes his situation acutely, namely the double attachment to Linossier and Chanlaire and the opposition between two outcomes, one heterosexual, the other homosexual. The move from the ‘amitié amoureuse’ for Raymonde to the ‘désir amoureux’ for Richard, the terrifying descent into his inner being, the experience of the vanity of things, such as the loss of the person he had been and which he believed he was, these are accompanied by the discovery of another self.

(…)

This loss of identity was to have immediate repercussions on the musical front. But at the same time, meeting Chanlaire did at least offer hope, and gave Poulenc a sympathetic ear outside the people most nearly concerned in his relations with Raymonde.

(…) Whereas his love for Raymonde had been kept secret even from its object, over Richard he ‘came out’ unreservedly in letters to friends such as Valentine Hugo and Wanda Landowska.

The financial crisis of 1929 renewed the role of the aristocracy in promoting new music.

The historian Michel Duchesneau comments that ‘the Society’s concerts constituted a kind of general, public “salon” that ensured visibility on a grand scale for a certain group of the Parisian aristocracy, while satisfying aspirations that were in clear contradiction with social currents in France at the time’. It was of course the case that in 1931 France was only five years away from the rise to power of the left-wing Front National. But it was also the case that the French aristocracy, like aristocracies through the ages, held much of their wealth in the form of land and so were less seriously affected by the Wall Street Crash than those who relied on the money markets. Given that the French government would not normally commission new music until the Exposition of 1937 (Berlioz’s Requiem and Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale a century earlier had been almost the exceptions that proved the rule), it could be argued that the aristocracy were taking on a social duty that no other group either would or could fulfil, least of all in 1931 which marked the peak of the financial crisis in France.

In mid-May, with Le Grand Coteau (Note: Poulenc’s country residence) apparently reprieved, it was the venue for a Whitsun weekend party including Rieti and Sauguet, and Prokofiev and Auric and their wives. Bridge seems to have played a role. This would also seem to have been the weekend Poulenc remembered with some sadness thirty years later (with slightly later dates) as the last in a long series of Parisian bridge evenings with Prokofiev through 1931 and 1932. This time the meeting extended almost to a whole week, in which the two of them also rehearsed together (on two pianos?) in the Salle Gaveau. Poulenc then saw Prokofiev on to his bus, said ‘Write!’ . . . and never saw or heard from the Russian again.

V SURREALISM AND FAITH 1934–1939

Two of Poulenc’s most interesting literary contributions appeared during October 1935. ‘Mes maîtres et mes amis’, published that month in Conferencia, had been given as a talk on 15 March with music performed by Maria Modrakowska and five wind players, and offers a good idea of his tastes and preoccupations: a spring away from Paris (the 16th arrondissement aside) was a spring wasted; his favourite composers were Mozart, Schubert, Chopin, Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky; those who had ‘never touched my heart’ included Wagner, Brahms and Fauré; painting is, together with music, the art to which he’s most responsive; as for jazz, he listens to it in the bath, ‘but for me it’s frankly odious in a concert hall’; and ‘I need a certain musical vulgarity as a plant desires compost.’ He followed up this last admission with an article provocatively entitled ‘Éloge de la banalité’. Writing to prepare audiences for performances in Lausanne and Geneva of Le Bal masqué, he explained first of all that he was not a composer who created his own syntax, but one who ‘arranged known materials in a new order’. He warned that ‘In our day, when we must have the new at any price, the taste for a system has found its way into painting as well as music, with a rigour that threatens to become instantly old hat.’ A saying of Picasso, echoing both Cocteau and Ravel, won his admiration: ‘The truly original artist is the one who never manages to copy exactly’; and on the subject of banality so did two quotations from Max Jacob’s Art poétique: ‘Authors who make themselves obscure in order to win esteem get what they want and nothing more’ and ‘There is a purity of the guts which is rare and excellent.’

Reaching some kind of truth about Poulenc’s religious life is far from easy: the evidence is scattered and sometimes contradictory, his attitude depends to no small extent on his mood, and clearly he finds it a hard thing to describe in words – which is certainly not to say that his religious feelings were faked. One thing we can say with certainty is that visiting the Black Virgin and taking back with him the little pamphlet which a few days later would inspire the Litanies à la Vierge noire offered not only immediate comfort but also the glimpse of a way forward. As Yvonne Gouverné wrote many years later, ‘Nothing seemed to happen and yet everything changed within Poulenc’s spiritual life.’ But even she found it hard entirely to grasp the nature of the event. Shortly before her death she was asked about Poulenc’s ‘return to the faith’. At this, her charm turning abruptly to severity, she proclaimed ‘On ne fait pas de retour à la foi.’ In saying this she was following the precept of St Francis Xavier, already quoted in Chapter 1: ‘Give me a child until he is seven, and I will show you the man.’ If this is true, then Poulenc had, from baptism and confirmation, remained a Catholic at his core whatever the impact of superficial events. It was therefore not a return, but an epiphany, the reappearance of something long hidden beneath worldly cares.

As for Poulenc’s newly found ‘sacred style’, this was to be a major item in the composer’s gallery of musical costumes, often together with a repetitive, litany-like structure towards which Éluard’s poetry also tended. In the course of a fascinating article on the cycle, Sidney Buckland notes that in it ‘Images of darkness and light, strength and frailty, obstacle and ease abound, interact, unite. All move towards the ecstatic “harmonisation of opposites” of the final poem’, and she ends her article by quoting from Éluard himself: ‘Everything is comparable to everything. Everything finds its echo, its reason, its likeness, its contrast, its perpetual becoming, everywhere. And that becoming is infinite.’48 The relevance to Poulenc of such inclusiveness is not hard to find – as Buckland says, he ‘lived in a constant state of reconciliation of opposites’: the juxtaposition of his new-found religious feeling with both his populist propensities and his homosexuality, of simple with complex harmonies in his musical language, and of outward ebullience with inner ‘inquiétude’.

The final event of that December was a particularly sad one. After years of struggling with a brain disorder (still not analysed to everyone’s satisfaction over eighty years later), in the early morning of 28 December Ravel died after an operation. Poulenc attended the civil funeral two days later in the cemetery of the north-western Paris district of Levallois-Perret, together with Jacques Rouché, Reynaldo Hahn, Ricardo Viñes, Milhaud and Stravinsky among others. Although never a member of Ravel’s intimate circle – the twenty-four years’ distance in age perhaps worked against this – Poulenc had remained an admirer since the Monte-Carlo premiere of L’Enfant et les sortilèges in March 1925 and always treasured Ravel’s remark that ‘Poulenc invents his own folklore’. If further testimony is needed of Poulenc’s affection, it can be found in the article he wrote in 1941, ‘Le coeur de Maurice Ravel’. Finding himself in January 1940 with a day to spare in Ravel’s home town St-Jean-de-Luz: I went into the church where the baby Maurice was baptized. In this Basque church, fitted with wooden balconies and where the word ‘nave’ truly recaptures its maritime meaning, it was already quite dark. A few candles were burning on the altar of the Virgin. Then Ravel, I prayed for you; do not smile, dear sceptic, because if I am sure you had a heart, I am even more certain that you had a soul.

Leave a comment