A few days ago, we read a few anecdotes to get acquainted with Robert Schumann. Today, let us hear a few stories about his friend Johannes Brahms…

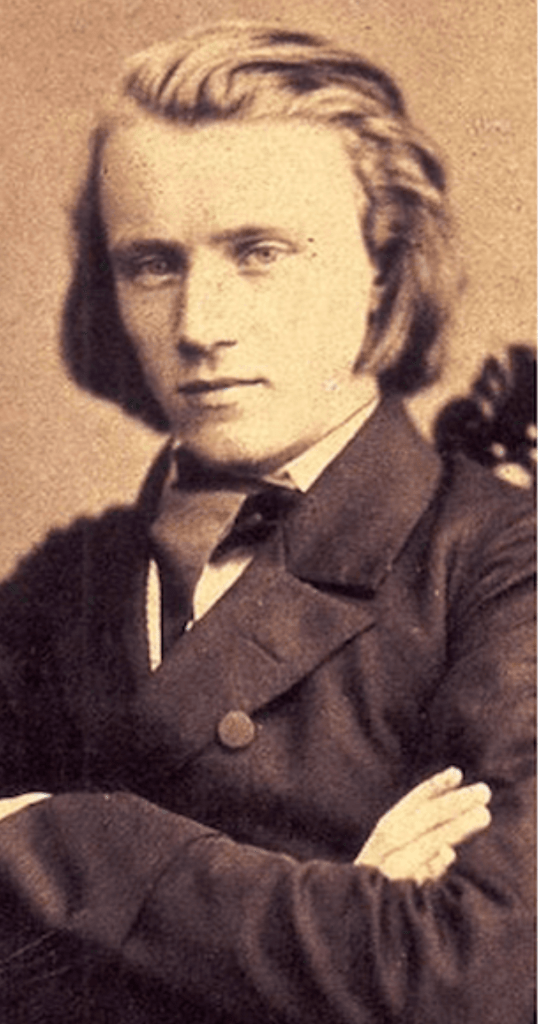

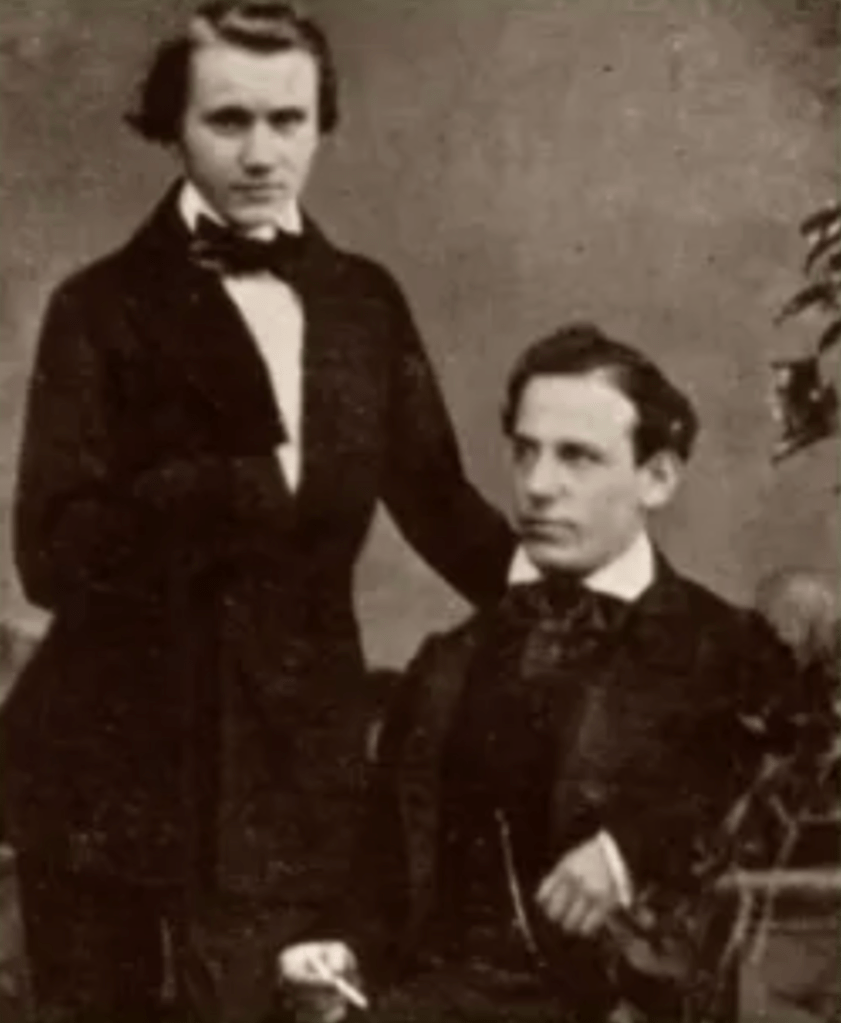

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-1897)

German symphonist who, like Beethoven, migrated to Vienna. His earliest musical activity was playing piano in squalid Hamburg taverns, until Joachim and Schumann recognized his ability.

On one evening early in June 1853, Liszt sent us* word to come up to the Altenburg next morning, as he expected a visit from a young man who was said to have great talent as a pianist and composer, and whose name was Johannes Brahms. We found Brahms and [Eduard] Reményi † already in the reception-room… I strolled over to a table on which were lying some manuscripts of music. They were several of Brahms’ unpublished compositions, and I began turning over the leaves of the uppermost in the pile. It was the piano solo Op. 4, Scherzo, E Flat Minor, and, as I remember, the writing was so illegible that I thought to myself that if I had occasion to study it I should be obliged first to make a copy of it. Finally Liszt came down, and after some general conversation he turned to Brahms and said: ‘We are interested to hear some of your compositions whenever you are ready and feel inclined to play them.’ Brahms, who was evidently very nervous, protested that it was quite impossible for him to play while in such a disconcerted state… Liszt, seeing that no progress was being made, went over to the table, and taking up the first piece at hand, the illegible scherzo, and saying, ‘Well, I shall have to play,’ placed the manuscript on the piano-desk…

He read it off in such a marvellous way – at the same time carrying on a running accompaniment of audible criticism of the music – that Brahms was amazed and delighted.. . A little later someone asked Liszt to play his own sonata, a work which was quite recent at that time, and of which he was very fond. Without hesitation, he sat down and began playing. As he progressed he came to a very expressive part of the sonata, which he always imbued with extreme pathos, and in which he looked for the especial interest and sympathy of his listeners. Casting a glance at Brahms, he found that the latter was dozing in his chair.

*The narrator is William Mason (1829-1908); American pianist.

† (1830-98); widely travelled Hungarian violinist who toured in 1852 with Brahms as

his accompanist.

——

The door [to the tavern] opened again, admitting a rush of snow and three more patrons. In contrast to the other newcomers, these last were eminently more suited to the environment, the feminine member of the trio being a well-known street-walker and inhabitant of this old and dark section of the city. Her escorts were gigolos and all were very drunk. They seated themselves at a table next to Brahms and his friends and ordered drinks – as if they had not already drunk enough – all of them. Suddenly above the talking, the ‘lady’ called over to Brahms: ‘Professor, play us some dance music. We want to dance.’ I* had the impression that she knew him, which is not unlikely, for Brahms, like Beethoven, was somewhat divided in his patronage of idealist companionship and the more downright variety found in dark and unfrequented streets. At any rate, he rose from the table and with slow and deliberate steps went toward the

old untuned piano which leaned against the dirty wall and began to play-waltzes, quadrilles – tunes which were for the most part passés and dated back a good many years. The lady who had succeeded so remarkably in getting Brahms to play, danced with her friends and others joined in. Brahms played uninterruptedly for an hour and then returned to his table, paid his bill and left. I have often thought the proprietor of this establishment should have put up a tablet in memory of this evening: ‘Brahms played dance music in this pub.

The following day I went to my coffee house and met an elderly gentleman who had been in Brahms’ party the night before. This was Mr Bela Haas, a well-to-do socialite famous for his wit. I said to him, ‘Please tell me what ever induced Brahms to play dance music for such a gathering,’ and he answered, ‘Well, I too was surprised and asked Brahms the same question. He told me, “When I was a boy in Hamburg I used to play in just such a place the whole night. I played dance music for drunken sailors and their girls. The place reminded me of that time and the pieces I played were those I used to play every night in Hamburg.”

* Max Graf (1873-1958), Austrian critic.

——

Early one morning * we were walking along the road which leads by the lake from Beatenbucht to Merligen, and had somehow come to speak of women and family life. Brahms said, ‘I have missed my chance. At the time I wished for it, I could not offer a wife what I should have felt was right.’ Upon my asking him, if by that he meant that he had lacked confidence in his power to keep wife and children by his art, he replied, ‘No, I did not mean that. But at the time when I should have liked to marry, my music was either hissed in the concert-rooms, or at least received with icy coldness. Now for myself, I could bear that quite well, because I knew its worth, and that some day the tables would be turned. And when, after such failures, I entered my lonely room I was not unhappy. On the contrary! But if, in such moments, I had had to meet the anxious, questioning eyes of a wife with the words “another failure” – I could not have borne that! For a woman may love an artist, whose wife she is, ever so much, and even do what is called believe in her husband – still she cannot have the perfect certainty of victory which is in his heart. And if she had wanted to comfort me… a wife to pity her husband for his non-success… ugh! I cannot hear to think what a hell that would have been, at least to me.”

Brahms uttered these words vehemently, in short, broken sentences, looking so defiant and indignant that I could think of no reply…. ‘It has been for the best,’ added Brahms, suddenly, and the next minute showed his usual expression of quiet content.

*The narrator is Joseph Viktor Widmann (1842-1911); Swiss journalist, friend of Brahms.

——

On the day before the concert there was, as usual, the final full rehearsal, to which in most places in Germany the public are admitted. Brahms had played Schumann’s Concerto in A Minor and missed a good many notes. So in the morning of the day of the

concert he went to the Concert Hall to practise. He had asked me* to follow him thither a little later and to rehearse with him the songs – his, of course he was to accompany for me in the evening. When I arrived at the hall I found him quite alone, seated at the piano and working away for all he was worth, on Beethoven’s Choral Fantasia and Schumann’s Concerto. He was quite red in the face, and, interrupting himself for a moment on seeing me stand beside him, said with that childlike, confiding expression in his eyes, ‘Really, this is too bad. Those people tonight expect to hear something especially good, and here I am likely to give them a hoggish mess. I assure you, I could play to-day, with the greatest ease, far more difficult things, with wider stretches for the fingers, my own concerto for example, but those simple diatonic runs are exasperating. I keep saying to myself: “But, Johannes, pull yourself together, do play decently,” but no use; it’s really horrid.’

*Sir George Henschel (1850-1934); conductor and baritone.

——

At a Philharmonic rehearsal. . . at which one of his Serenades was played, the orchestra grew visibly restless, indicating disapproval of this composition. Brahms stepped to the director’s stand and said, ‘Gentlemen, I am aware that I am not Beethoven – but I am Johannes Brahms.’

——

Joachim, in a few well-chosen words, was asking us not to lose the opportunity of drinking the health of the greatest composer, when, before he could finish the sentence, Brahms bounded to his feet, glass in hand, and called out, ‘Quite right! Here’s Mozart’s health!’ and walked round, clinking glasses with us all.

——

‘Yes, gentlemen,’ observed [his Coblenz host] solemnly as the guests sat in almost reverential silence, inhaling the bouquet of some rare old Rauenthaler that had been reserved for the end of the repast, ‘what Brahms is among the composers, so is this Rauenthaler among the wines.’ ‘Ah, then let’s have a bottle of Bach now,’ cried Brahms.

——

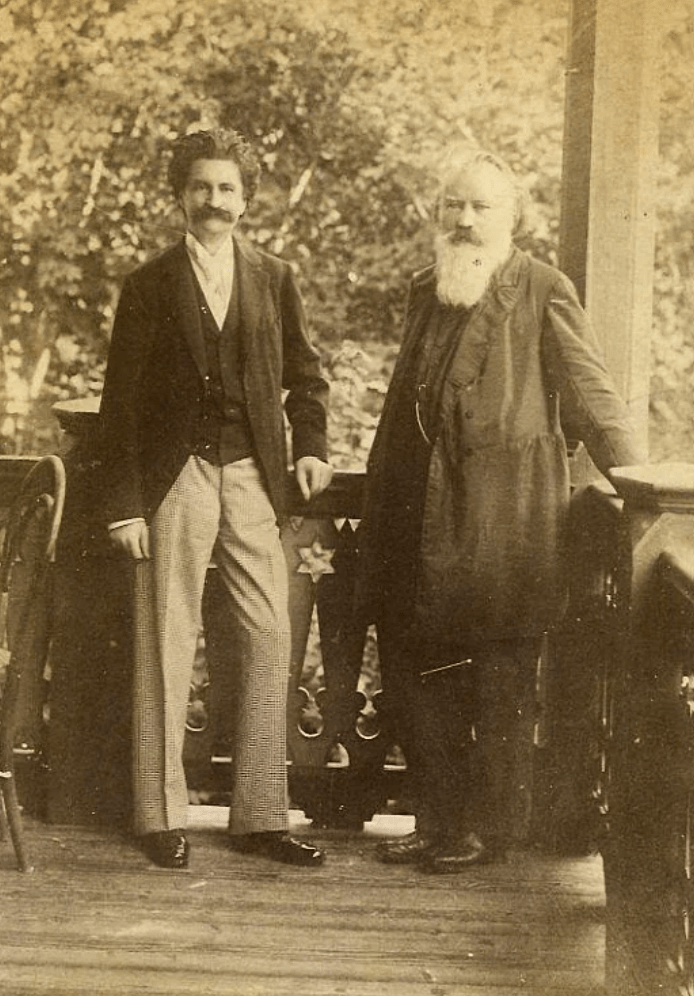

He was a great walker, and had a passionate love of nature. It was his habit during the spring and summer to rise at four or five o’clock, and, after making himself a cup of coffee, to go into the woods to enjoy the delicious freshness of early morning and to listen to the singing of the birds. In adverse weather he could still find something to admire and enjoy.

‘I never feel it dull,’ he said one day, in answer to some remark about the depressing effect of the long-continued rain, ‘my view is so fine. Even when it rains, I have only another kind of beauty….

‘How can I most quickly improve?’ I asked him one day. ‘You must walk constantly in the forest,’ he answered; and he meant what he said to be taken literally.

*Florence May (1845-1923); English pianist.

——

After many hours of wandering [in the Vienna Woods] he and his friends had come to an inn and asked for black coffee. The coffee was made with chicory – an economy exercised by many cooks – and Brahms did not like chicory in his coffee. He called the proprietress to his table and said, ‘My dear old lady, have you some chicory?’

When she said she had, he continued in an even more gracious tone, ‘It’s not possible! May I see it?’ The old woman retreated to the kitchen and returned with two packages of chicory which she handed to Brahms. He looked them over solemnly and inquired, ‘Is that all you have?’ When she said yes, he pocketed both boxes and said, ‘Well, now you can go back and make us some black coffee.’

——

We ** retired to room No. 11, and it was my instant and most ardent endeavour to go to sleep before Brahms did, as I knew from past experience that otherwise his impertinently healthy habit of snoring would mean death to any hope of sleep on my part. My delight at seeing him take up a book and read in bed was equalled only by my horror when, after a few minutes, I saw him blow out the light of his candle. A few seconds later the room was fairly ringing with the most unearthly noises issuing from his nasal and vocal organs. What should I do? I was in despair, for I wanted sleep, and moreover, had to leave for Berlin early next morning. A sudden inspiration made me remember room No. 42. I got up, and went downstairs to the lodge of the porter, whom, not without some difficulty, I succeeded in rousing from a sound sleep. Explaining cause and object, I made him open room No. 42 for me. After a good night’s rest, I returned, early in the morning, to the room in which I had left Brahms.

He was awake and, affectionately looking at me, with the familiar little twinkle in his eye and mock seriousness in his voice, said to me, well knowing what had driven me away, ‘Oh, Henschel, when I awoke and found your bed empty, I said to myself, “There! he’s gone and hanged himself!’ But really, why didn’t you throw a boot at me?”

The idea of my throwing a boot at Brahms!

**The narrator is Sir George Henschel.

——

Karl Goldmark (1830-1915), composer and friend of Brahms

Brahms was built on big lines and was absolutely truthful. He could not tell even the ordinary conventional fib. His friends were as wax in his hands. He was as great a man as he was an artist. There was not a blot on his superb character. But he was never accustomed to restraining himself nor to holding his tongue. If he disliked anything he would say so frankly. This bluntness combined with his rough manner frequently made him appear very harsh.

The following remark of some wit was current in Vienna. One evening, Brahms, on taking leave of his hostess at a party, said, ‘Kindly excuse me if I by chance have forgotten to offend one of your guests.

——

On one occasion Brahms, Goldmark and myself* had dined with Ignaz Brull’s father, Siegmund Brüll, and after dinner we retired for a smoke. A few recently published compositions by Ignaz were lying on the piano. Brahms turned over the leaves and suddenly exclaimed, “How beautiful, how very beautiful!” (Modest Ignaz was doubtless silently enchanted.) But Brahms continued, ‘It is the most beautiful title-page I have seen for a long time!’

- Sir Felix Semon, British laryngologist; Ignaz Brull (1846-1907); Austrian composer.

——

After Dvořák had sent him a work which was not flawless in its workmanship, he answered, “We cannot any longer write as beautiful music as Mozart did; so let us try to write as clean.’

——

At Leipzig he was always a little ‘out of tune’. He never quite forgave the first reception of his D minor Concerto at the Gewandhaus, and he used to vent his bottled-up wrath by satirical remarks to the Directors. One of them, a tall and rather pompous gentleman who wore a white waistcoat, asked Brahms before the concert with a patronizing smile, “Whither are you going to lead us tonight, Mr Brahms? To Heaven?’

Brahms: ‘It’s all the same to me which direction you take.’

——

Brahms knew, and was well known to, all the children of the neighbourhood, and when starting on his country walks would fill his pockets with sweetmeats and little pictures, and amuse himself with the eagerness of the small bare-footed folk, who knew his ways

and would run after him as he passed, on the look out for booty. ‘Whoever can jump gets a gulden,’ he would say; and, displaying beyond reach of the little ones a handful of sweatmeats made in imitation of the Austrian coin, he would increase his speed, and raise his hand higher and higher, drawing after him the flock of running, leaping children, until he allowed one and another to gain a prize.

——

I* can remember Bülow reproaching Brahms for sending the manuscript of the Fourth Symphony, of which no copy existed, as an ordinary postal packet, not even registered. ‘What would we have done had the packet gone astray?’ The composer answered: ‘In that case I would have had to write the Symphony anew.”

*Frederic Lamond (1868-1948); British pianist.

——

Brahms, received the telegram [announcing Clara Schumann’s death] in Vienna stating that the funeral was to take place in Endenich, near Bonn, and that she was to be buried beside her husband. He travelled to Frankfort-on-the-Maine to catch the connection. In Frankfort a railway official foolishly told him to take the train running on the right side of the Rhine, instead of the left side, with the result that Brahms arrived too late in Endenich to be present at the funeral. The chagrin, the vexation, made him feel ill and sick: he, who had never known a day’s illness, did not recognize himself in the looking-glass the next morning. An attack of jaundice had set in overnight.

——

Brahms made to attend the funeral of his old adversary Bruckner, in October 1896, but turned back at the cathedral door. ‘Never mind,’ he was heard to say, ‘Soon my coffin.’

Leave a comment