After ordering his dinner with his funny old cook and telling his nephew to see to the wine, we all five took a walk. Beethoven was generally in advance humming some passage. He usually sketches his subjects in the open air; it was on one of these occasions, Schuppanzigh* told me, that he caught his deafness. He was writing in a garden and was so absorbed that he was not sensible of a pouring rain, till his music paper was so wet that he could no longer write. From that day his deafness commenced, which neither art nor time has cured.

- Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1776-1830); leader of string quartet at Rasoumovsky’s,

introduced several new Beethoven works.

Beethoven was playing a new Pianoforte Concerto of his, but forgot at the first tutti, that he was a Soloplayer and springing up, began to direct in his usual way. At the first sforzando he threw out his arms so wide asunder, that he knocked both the lights off the piano upon the ground. The audience laughed, and Beethoven was so incensed at

this disturbance, that he made the orchestra cease playing, and begin anew. Seyfried, fearing, that a repetition of the accident would occur at the same passage, bade two boys of the chorus place themselves on either side of Beethoven, and hold the lights in their hands. One of the boys innocently approached nearer, and was reading also in the notes of the piano-part. When therefore the fatal sforzando came, he received from Beethoven’s out thrown right hand so smart a blow on the mouth, that the poor boy let fall the light from terror. The other boy, more cautious, had followed with anxious eyes every motion of Beethoven, and by stooping suddenly at the eventful moment he avoided the slap on the mouth. If the public were unable to restrain their laughter before, they could now much less, and broke out into a regular bacchanalian roar. Beethoven got into such a rage, that at the first chords of the solo, half a dozen strings broke. Every endeavour of the real lovers of music to restore calm and attention were for the moment fruitless. The first allegro of the Concerto was therefore lost to the public. From that fatal evening Beethoven would not give another concert.

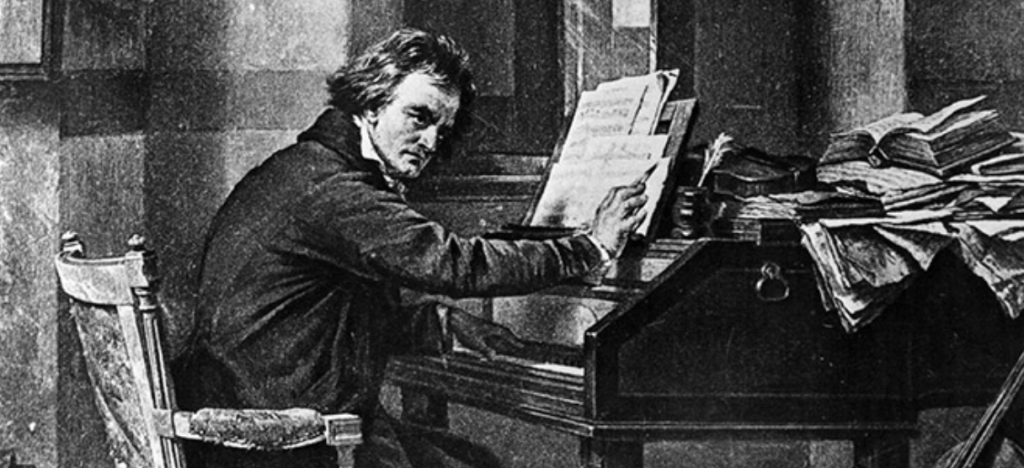

We went one afternoon to the Alservorstadt, and mounted to the second storey of the so-called Schwarzspanier house. We rang, none answered; we lifted the latch, the door was open, the ante-room empty. We knocked at the door of Beethoven’s room, and receiving no reply, repeated our knock more loudly. But we got no answer, although we could hear there was someone inside. We entered, and what a scene presented itself! The wall facing us was hung with huge sheets of paper covered with charcoal marks; Beethoven was standing before it, with his back turned towards us, but in what a condition! Oppressed by the excessive heat, he had divested himself of everything but his shirt, and was busily employed writing notes on the wall with a lead pencil, beating time and striking a few chords on his stringless pianoforte. He did not once turn towards the door. We looked at each other in amused perplexity. It was no use trying to attract the deaf master’s attention by making a noise; and he would have felt embarrassed had we gone up to him. I said to Atterbom, ‘Would you, as a poet, like to take away with you to the north the consciousness of having, perhaps, arrested the loftiest flights of genius? You can at least say, “I have seen Beethoven create.” Let us

leave, unseen and unheard!’ We departed. We had certainly caught him in flagrante.

*Alois Jeitteles, Austrian poet, author of An die Ferne Geliebte cycle, set by Beethoven: Per Daniel Amadeus Atterbom (1790-1855); Swedish poet and philosopher.

Goethe, letter to Zelter

Karlsbad, 2 September 1812

I made the acquaintance of Beethoven in Teplitz. His talent amazed me. However, unfortunately he is an utterly untamed personality, not entirely in the wrong if he finds the world detestable, but does not thereby make it more enjoyable for himself or for others.

Beethoven, letter to Bettina von Arnimt*

When two such come together as I and Goethe great lords must note what it is that passes for greatness with such as we. Yesterday, as we were returning homewards, we met the whole Imperial family; we saw them coming at some distance, whereupon Goethe disengaged himself from my arm, in order that he might stand aside; in spite of all I could say, I could not bring him a step forwards. I crushed my hat more furiously on my head, buttoned up my top coat, and walked with my arms folded behind me, right through the thickest of the crowd. Princes and officials made a lane for me: Archduke Rudolph took off his hat. The Empress saluted me the first: – these great people know me! It was the greatest fun in the world to me, to see the procession file past Goethe. He stood aside, with his hat off, bending his head down as low as possible. For this I afterwards called him over the coals properly and without mercy.

*(1785-1859); recipient of Goethe’s Correspondence with a Child and, briefly, a love-

object of Beethoven’s. The autograph of this letter has never been traced and its dates conflict with known events, but the story appears to have some basis in fact.

One summer… I* frequently visited my grandmother, who had a country-house in … Döbling; Beethoven was at Döbling at the same time. Opposite to my grandmother’s windows was the tumbledown house of a peasant, named Flohberger, notorious for his profligate life. Besides his unsightly dwelling, Flohberger had a daughter with a very pretty face, but not a very good reputation. Beethoven seemed to take great interest in this girl; I can still see him walking along the Hirschengasse, with his white handkerchief in his right hand trailing along the ground, stopping at Flohberger’s yard gate, behind which the giddy girl was working vigorously with a fork on the top of a waggon of hay or manure, laughing incessantly. I never saw Beethoven speak to her; he used to stand silently gazing, till the girl, who preferred the company of peasant lads, would vex him with a jeer, or persistently take no notice. Then he would suddenly dash off, but he never failed to stop there the next time he passed. His interest was so intense that when the girl’s father was thrown into the village jail (called the Kotter) on account of a drunken brawl, he interceded personally for his release. But, in his fashion, he treated the parish authorities so brusquely that he very nearly became the involuntary companion of his imprisoned protégé.

* Franz Grillparzer (1791-1872); Austrian dramatist and poet.

One evening, on coming to Baden to continue my lessons, I* found Beethoven sitting on the sofa, a young and handsome lady beside him. Afraid of intruding my presence, which I judged might be unwelcome, I was going to withdraw, but Beethoven prevented me, saying, ‘You can play in the mean time.’ He and the lady remained seated behind me. I had been playing for some time, when Beethoven suddenly exclaimed, ‘Ries, play us an Amoroso,’ shortly after, ‘a Malinconico,’ then an ‘Appassionato,’ &c. From what I heard I could guess that he had in some way given offence to the lady, and was now trying to make up for it by such whimsical conduct. At last he started up, crying, ‘Why that is my own, every bit!’ I had all along been playing extracts from his own works, linked together by short transitions, and thus seemed to have pleased him. The lady soon left, and I found to my utter astonishment that Beethoven did not know who she was.

*Ferdinand Ries, German musician and Beethoven’s biographer

Professor Höfel, .. was one evening with Eisner (still living in Vienna) and others of his colleagues; also the Police Commissary of W[iener] Neustadt, in the garden of the Wirthshaus ‘Zum Schleifen, a little way out of town. It was autumn and already dark when a constable came out and said to the commissary, ‘Herr Commissär, wir haben Jemand arretirt welcher uns kein’ Ruh gibt. Er schreit immer dass er der Beethoven sei. Er ist aber ein Lump, hat kein Hut, alter Rock, etc., kein Aufweis wer er ist, etc.’ (Mr Commissary, we have arrested one who will give us no peace. He keeps on yelling that he is Beethoven. But he’s a ragamuffin; has no hat, an old coat, etc.; nothing by which he can be identified.)

The Commissär ordered that the man be kept in arrest until morning, ‘dann werden wir verhören wer er ist’ (then we will examine him and learn who he is). Next morning the company was very anxious to know how the affair turned out, and the Commissary said that about 11 o’cock he was woken up by a policeman with the information that the prisoner gave them no peace, and demanded that Herzog, Musikdirektor in Wiener Neustadt, be called to identify him. So the Commissary got up, dressed, went out and waked up Herzog, and, in the middle of the night, went with him to the watchhouse. Herzog, as soon as he cast eyes upon the man exclaimed, ‘Das ist der Beethoven!’ (That is Beethoven.) He took him home with him, gave him his best room, etc. Next day came the Bürgermeister, making all sorts of apologies. As it turned out Beethoven had got up early in the morning, and slipping on a miserable old coat, and without a hat, had gone out to walk a little… He had been seen looking in at the windows of the houses, and as he looked so like a beggar the people had called a constable and arrested him. Upon his arrest the composer said, ‘Ich bin Beethoven’ (I am Beethoven). ‘Warum nich gar?’ (Of course, why not?) said the policeman, ‘ein Lump sind sie; so sieht der Beethoven nicht aus’ (You’re a tramp; Beethoven doesn’t look like that.)

Schindler tells us that Beethoven copied out three ancient Egyptian inscriptions ‘and kept them framed and mounted under glass, on his work table.’ The first two of these read:

I AM THAT WHICH IS.

I AM EVERYTHING THAT IS, THAT WAS, AND THAT WILL BE. NO MORTAL MAN HAS LIFTED MY VEIL.

And the third:

HE IS OF HIMSELF ALONE, AND IT IS TO THIS ALONENESS THAT ALL THINGS OWE THEIR BEING.

When Beethoven heard, in the last days of his life, that Hummel* was expected at Vienna, he was overjoyed, and said, ‘Oh! if he would but call to see me!’ Hummel did call, the very day after his arrival,… and the meeting of the old friends, after they had not seen each other for so many years, was extremely affecting. Hummel, struck by Beethoven’s suffering looks, wept bitterly. Beethoven strove to appease him, by holding out to him a drawing of the house at Rohrau in which Haydn was born, sent to him that morning by Diabelli, with the words, ‘Look, my dear Hummel, here is Haydn’s birthplace; it is a present that I received this morning, and it gives me very great pleasure. So great a man born in so mean a cottage!’ Hummel afterwards paid him several visits; ten or twelve days afterwards Beethoven expired, and Hummel attended him to the grave.

*Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837); composer and pianist.

Early in the afternoon of 26 March Hüttenbrennert went into the dying man’s room. Beethoven had then long been senseless. Telscher began to draw the dying face of Beethoven. This grated on Breuning’s feelings, and he remonstrated with him…. Then Breuning: and Schindler left to go out to Währing to select a grave. The storm passed over, covering the Glacis with snow and sleet. As it passed away a flash of lightning lighted up everything. This was followed by an awful clap of thunder. Hüttenbrenner had been sitting on the side of the bed sustaining Beethoven’s head holding it up with his right arm. His breathing was already very much impeded, and he had been for hours dying. At this startling. awful peal of thunder, the dying man suddenly raised his head from Hüttenbrenner’s arm stretched out his own right arm majestically- ‘like a General giving orders to an army’. This was but for an instant; the arm sunk back; he fell back. Beethoven was dead.

Source of the anecdotes: The Book of Musical Anecdotes by Norman Lebrecht (The Free Press, 1985)

Leave a comment