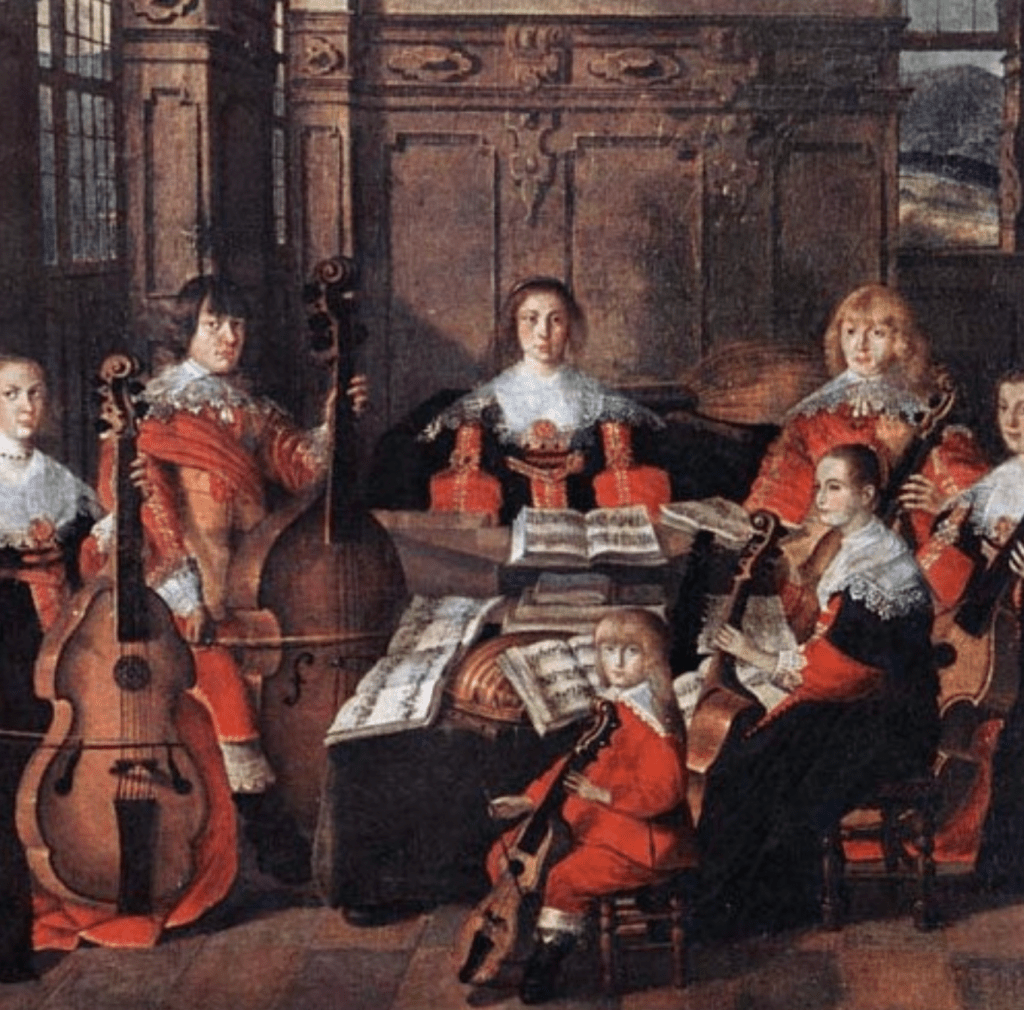

Music is a language, and chamber music is a conversation. The conversation did not start in the 18th century. This post takes us to the 17th century, when the violin replaced the treble viol in European courts…

The text below is an excerpt from “The Weapons of Rhetoric, a guide for musicians and audiences” by Judy Tarling (p. 61-62)

Instrumental choice and social status

‘Speaking appropriately’ during the Renaissance period also encompassed the matching of social status with the choice of instrument. Princes and courtiers preferred stringed instruments to wind instruments as the latter distorted the face and blocked the mouth, and therefore prevented speech. This idea from Aristotle (Politics Book VIII) was endorsed by Plato (The Republic Part Three 399e) and perpetuated through the writings of Plutarch (Life of Alcibiades) and in the sixteenth-century Castiglione, who thought wind instruments unsuitable for women to play. The discrediting of wind instruments was in part based on the myth of the triumph of the string player Apollo over the wind-player Marsyas, who having lost the contest was flayed alive. Fretted instruments such as the lute and viol were preferred to the violin family, which in the sixteenth century was only played by servants, mostly for dancing, and were not considered suitable for a gentleman to play.

We call viols those instruments with which gentlemen, merchants and other virtuous people pass their time… the other type is called violin; it is commonly used for dancing.(Jambe de Fer, Epitome Musical (1556), tr. Riley, p. 59.)

Naturally, the repertoire associated with these two families of instruments reflected their characters: dance music for the violin, more serious contrapuntal music for the viol consort. Large professional bands of instruments of the violin family were used for public ceremonial occasions such as coronations while the viol consort was normally heard only in private, either at court or in domestic music-making. The visual effect was as important as the type of music performed. Noble amateur musicians usually played either alone or to a small number of people in a private room, and elegant posture constituted a major part of the performance. The Burwell Lute Tutor describes the elegant position of the body when playing the lute, also commented upon by Mattheson, which was to the advantage of the player:

The lute has a great advantage over other instruments and if it does not improve them at least it doth bring forth their beauty and ingage those that play upon the lute to give them all that art can add to nature. All the actions that one does in playing of the lute are handsome, the posture is modest free and gallant and do not hinder society. When one plays of the virginall he turns his back to the company. The violl intangleth one in spreading the arms and openeth the legges which doth not become man, much lesse woman.The Burwell Lute Tutor (1660-72), f. 69, 43v.

Instruments such as the violin, recorder and flute were not taken up by gentlemen until the latter part of the seventeenth century, when they became more socially acceptable for amateur music-making. Gentlemen amateurs formed informal private chamber music clubs, such as those which operated in Oxford during the Interregnum. A sense of decorum forced these players to withdraw from performing when the concerts became open to a paying audience, who may perhaps have been the same gentlemen who formerly played in private. Elyot felt that ‘a gentilman, plainge or singing in a commune audience [i.e. in public] appaireth [spoils] his estimation: the people forgettinge reverence, when they beholde him in the similitude of a common servant or minstrell’.

Roger North describes how, following a performance by Baltzar, a north German violinist who had worked at the Swedish court, the gentlemen of the English court ‘fell in pesle mesle, and soon thrust out the treble viol’. Baltzar was subsequently appointed to the King’s Private Musick at an extraordinarily high salary and following his success, the violin became an acceptable instrument for a man of leisure. Soon after the proud Italian virtuoso violinist Nicola Matteis came to England he was reduced by poverty to teaching gentlemen pupils. When playing in consort the socially superior pupils became upset if he did not allow them to take the best parts. When amateur and professional players sat down together to play, the gentlemen became annoyed at being outshone by players who also prostituted themselves in alehouses and theatres. North attributed the decline in amateur music making to the increase in public performances, declaring that ‘An ostentatious pride hath taken Appollo’s chair’.

Leave a comment